Interview by Astrid Hald

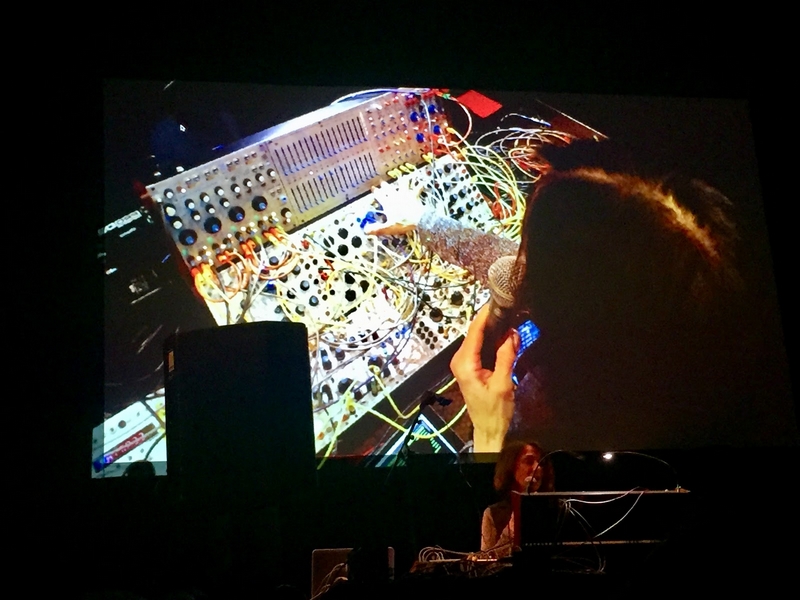

Iconic composer and sound designer extraordinaire Suzanne Ciani made her way by Malmö this spring to give a live quadraphonic performance at the culture house Inkonst, dedicated to experimental art and music. While being classically trained American Ciani entered the forefront of the world of electronics in the ‘60s when encountering synthesizer pioneer Don Buchla and thus the Buchla analogue modular synthesizer – the instrument which has become inseparable from her name ever since. After debuting with the experimental “Voices of Packaged Souls” in 1970 she has produced an endless string of masterpieces, all of which have contributed to the expansion and humanisation of the experience of electronic sound – and earned her 5 Grammy-nominations over time – through albums, films scores and commercials, such as one of her iconic ‘voice-over’ to the computerised washing machine.

After a 40 year break from performing live with the Buchla, she returned in 2016 and has been touring on and off since then. But no performance is a given, she tells Passive/Aggressive. “The day it breaks is the day I stop. It’s not an automatic thing like, “oh, you’re gonna do another Buchla concert?” It’s like am I gonna do another?”

Ahead of her performance, we sat down with her for a conversation about being a female pioneer that has paved the way for a new generation of analogue aficionados.

P/A: You were doing your degree in classical composition at Berkeley when you got interested in the world of electronic music and sound. What was it that drew you?

Suzanne Ciani: “It’s kind of a big jump to go from a classical background to throwing out all that and focusing on this instrument. I think it’s because I thought of myself as a composer primarily, and it was an interesting time in the late sixties. Women were just having this peak of emancipation. There were demonstrations, and we were going against the Vietnamese war. It was just a whole revolutionary mindset.

Then I met my boyfriend at the time, I call him ‘crazy Joseph’, and we lived in a place that was like a big womb. It had this visionary wall on it that looked like infinity made of this layered of moulded plastic. The whole place was soft and there were no walls… So I was already in this alternative reality and I met Don Buchla and went to his studio, which was just another magical world.”

P/A: What was it opposed to?

SC: “To be a proper modern composer you had to do something so difficult, that showed how great you were. Modern music was dreadful to me. It just got more and more separated from the human, the psyche. They were systems, like twelve tones systems. It wasn’t about expressing anything.

Electronic music liberated me from all of that because in electronic music or computer music nothing is difficult. It’s not limited by the technique of the human performer. So it might be really hard for a human performer to play you know 56 notes in one second or something, but for a machine, it’s no problem. All of that was not important… There is no longer a goal to prove yourself better or higher. It’s not about what can you do, but what do you wanna say? And that’s a different starting point from ‘how good can I make myself look?’”

P/A: You mentioned how women were experiencing a peak of emancipation. What was it like for you being a female composer in those years?

SC: “You know, I had a conducting class and I would be conducting. I was so thrilled to be doing this that I loved, and my professor said to me one time “you know, women have no place on the podium” It’s helpless to study conducting with somebody who thinks you got no right… They really weren’t ready then. There have been these waves, and now we’re at the peak of another one.”

P/A: What were your experience working with Don Buchla?

SC: “Difficult. I was fired on the first day. I went to work there and at the end of the day, they tested some of the boards. I was assembling boards and they found a cold solder joint and said: “well, must be the new girl” and so boom, you’re out. And I said, “ah ah, you can’t fire me!”.

So I showed up the next day and I just stayed… but it wasn’t easy. None of the people who worked there was electronic people. There was an Indian dancer, there was a philosopher. So I said, “Don, I really want to learn more about what this is”. And there were no books, so we started a class… We were like five people, and I was the only girl. At the end of the class, he said: “now don’t take this personally, but we’ve decided not to have any women in the class.”…That was a life lesson to me because what I realized was that it wasn’t personal, it could have been any woman. Any woman was gonna make them uncomfortable – they feel threatened.”

P/A: Now, how do you experience that?

SC: “I’m teaching now in the Berkeley college of music in Electronic Production and Design. Women are a very small minority. In one class there’ll be one woman and fifteen guys and just that proportion causes discomfort for the woman. So we decided to do a class for just women. The first thing they did was doing an emotional dump about what was going on, and it’s just what you expect. How subtle the communications are about your validity. It’s as simple as two people, a guy and a girl, sitting in a workstation of an analogue modular and the girl reaches up to turn a knob, and the guy says “oh let me show you how to do that”. And she is completely disempowered.

Then I gave a class with just the men and I said, “you know, you may not realize, that when you take the aggressive role, you’re basically burying this other person”… Women for a long time thought they weren’t good enough, they said: “if we just get really good, then it’ll be ok”. And so women got really good and nothing changed.

It’s not about your ability, it’s about the comfort zone, it’s a sociological thing.

One of the advances that women have made is to realize that there is room for them. In the early days, there was this sense of competition and we thought the openings were in the man’s world. Now they’re not competing. They’re supporting each other and that relaxes everything and allows this critical mass of power to start happening.”

Last year Suzanne Ciani released “Live Quadrophonic”, a live recording of her first Buchla performance in 40 years, from 2016 in San Francisco. Throughout her career, she has played the Buchla exclusively in quadrophonic.

P/A: Your understanding of spatiality in music has been far ahead of its time from the very beginning – can you tell me a bit about your view on this?

SC: “I grew up in that. Don Buchla made the first spatial modulator. That was always part of the instrument. We always played in quad. So for me coming back to it is kind of like riding a bicycle, and I’m lucky cause I have tools that he gave me to do that.

Electronic sound was meant to move, essentially it’s monophonic, it’s only when it moves it fulfils its destiny. Many other instruments don’t wanna move, you know a flute doesn’t wanna move… It was frustrating to me the first time quadraphonic recordings happened, nobody knew what to do with it. A lot of the people who were booking me were saying “what is quadraphonic?”. I worked hard with speaker companies to try to promote this new format and to get it into theatres so you could do it.

When I started playing this thing I thought, “oh, everybody will have one.”And that wasn’t a new idea. In the ’20s they thought everybody would have a theremin, and that it would be part of the standard orchestra. It’s the same visionary frustrations.”

P/A: In terms of recognition on the spatial aspect – what’s the situation like today?

SC: “It’s like 40 years later, and it is time. I just released a quad album LP and multi-speaker installations are happening every place, but it still hasn’t happened very much in live modular. Because nobody has a modular. One reason why I’m out playing is that I want the designers to see what you can do. I’m trying to say we could live forever of what he’s already done. His designs are so far ahead that there is this huge gap still, between what’s coming out and what could come out… It isn’t about time, it isn’t “that was back then and now we’ve come a long way.” These are timeless concepts. The difference between the idea and the technological manifestations of the idea. You can use transistors and integrated circuits, you can use lasers and I don’t know what… but we have to separate those. People in technology sometimes gets sidetracked by technology.”

P/A: What’s gonna happen when the Buchla breaks?

SC: “I’ll go home and play a lot of tennis. That’s why I’m doing as much as I can now because I’m not gonna do this… I say that, but who knows what’s gonna happen. Subotnik is still in his 80s doing this. But I do live on that edge where I’m ready. The first time that’s what happened. I moved to New York, the instrument broke and that was it. It was absolutely traumatic, so I don’t want to go through that again. I’m ready.”

P/A: It does sound like a break-up in a way?

SC: “It is a relationship and just like in any relationship, I don’t know what will happen. You can’t freeze it. You can’t say “I want this forever”. Everything is always in motion. It’s not about stopping, it’s about navigating the evolutionary path, you know. Just staying on it.”

Info: Suzanne Ciani’s most recent release “Flowers of Evil” came out in June on Finders Keepers. It’s a previously unreleased work from 1969, based on an unheard adaptation of Charles Baudelaire’s Élévation, a section from the French poet’s 1857 work, “Flowers Of Evil”.