Sean McCann – “My pieces could be performed and interpreted by anyone interested. There is no exclusivity” (interview)

Interview by Peter Jørgensen

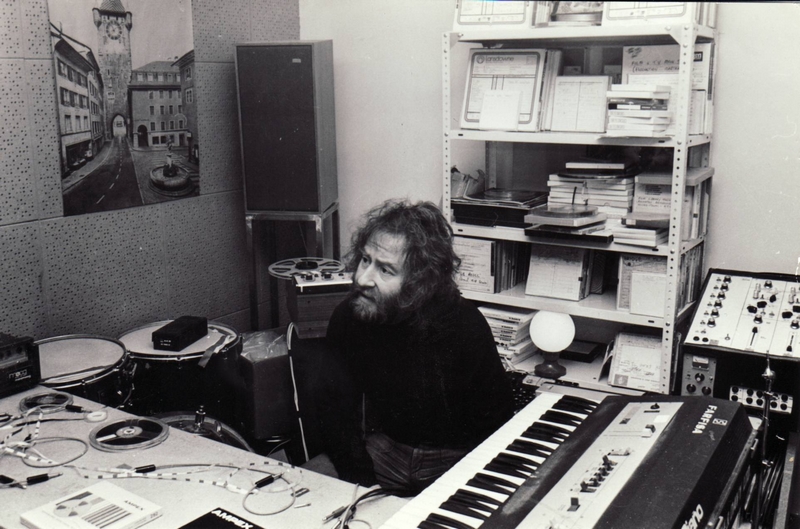

Following the output and inherent growth of composer Sean McCann has been a joyous ride for me for the past couple of years. His personal and fresh approach to composing and combining sound worlds has made for some of the past years’ most interesting releases. With the added bonus of being refreshingly ignorant of “the latest trend”.

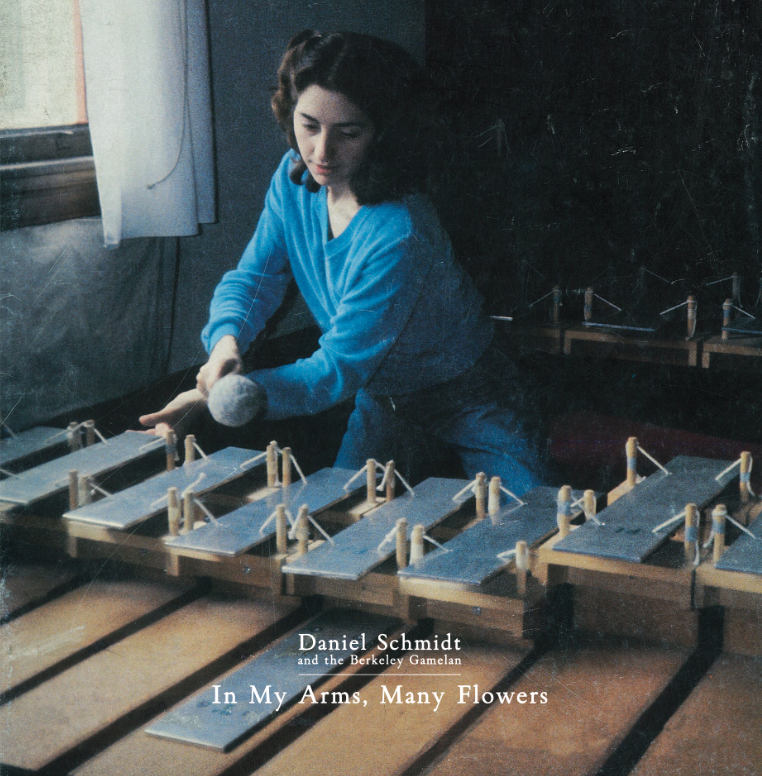

Besides his output as a composer, McCann (born 1988) has since 2012 curated an increasingly essential output on his own label, Recital. A wondrous and ever surprising combination of out-of-print half forgotten masterpieces such as Daniel Schmidt’s “In My Arms, Many Flowers” and Loren Connors’ “Airs”, intertwined with new offerings by the likes of omnipresent Sarah Davachi and McCann himself.

He has previously described his ambition with Recital to release “more focused, lasting music” and celebrate “what is significant and exciting in contemporary music”.

In the liner notes for the work “Pistons” he described himself as having “a hard time enjoying anything unless I am multitasking”. A statement which makes absolute sense to anyone who has listened to McCann’s liberating mixture of chamber orchestration, percussive elements, voices singing and reciting and more digitally processed, otherworldly sounds. While distinctly visceral and personal his works offer much space for the listener. To find one’s own place or perspective within the textures. For the listener, McCann’s microcosms of sound brings a sense of walking through a landscape. Being attentive to all sounds, attributing meaning, focus or importance by desire.

The music is at the same time easily accessible and quite complex. The pieces are loaded with hints and references, but feels freshly unacademic and full of life.

I’m always deeply fascinated when watching a real craftsman at work, performing his métier. I got interested in knowing more about what had shaped this output. What kind of musical upbringing did McCann have?

I got in touch with McCann to discover how he arrived where he is, and specifically, how he works.

PJ: I would like to start out by asking you to share a memory. Can you recall your first memory of sound? What and where it was?

SM: “I was young, perhaps three years old. My mother singing to me while I lay in bed, curled in blankets. An orange hall-light on leaking into the bedroom. In the dark and calm room, she was singing »…mama’s gonna buy you a mockingbird.«”

PJ: When was the first time you felt you created some music? Not just learned to play something on an instrument, but had the experience of making something of your own?

SM: “I became enamored with the software Fruity Loops when I was in 7th grade, and would spend all idle hours working on covers of Misfits songs or Smashing Pumpkins songs, I remember drawing out the entirety of “Porcelina of the Vast Oceans” on the piano-roll interface. This then morphed quickly into my own variations and emulations of those sorts of songs. Fruity Loops turned into an early DAW called Cakewalk, when I picked up real instruments and started making CDs for myself. I would make one copy of the album, print out artwork and paint covers, print out an insert. I recorded probably 12 albums of bedroom/strange/primal music, none of which will ever be heard by another person (for my sake and yours).

PJ: It seems to me creating the music and presenting the music has been two sides of the same coin from the start. Not only making a song, but recording it and presenting it in a given format.

Is that accurate and could you maybe elaborate on the interaction between composing and curating?

SM: “I am a plotter. I rarely work on anything without first preparing a home for it to live in. Decisive moves are made early on; it makes me happy to do it that way. Presentation is considered immediately. As a collector of shadow boxes, cataloguing and showcasing figures and ideas is comforting.”

PJ: How did you get into making music in the first place?

SM: “I started as a drummer in third grade, when I was about seven years old. Music is in my family; my parents love music and my sister is a pianist (I will be publishing a 7″ record by her this year on Recital). I played drums in reggae bands, punk bands, prog bands etc. It was in Jr. High School when I began branching out to other instruments, landing sweetly on my mother’s childhood viola.”

PJ: Have you formally studied composition?

SM: “No, I have not, but I have taught myself to notate and write scores (both formally and informally). I am glad I slid down the path I did (non-academically). Although, I’ll never know what would’ve happened had I studied John Adams or Robert Filliou in college. I’d probably be more bold.”

PJ: I had listened to a couple of your more drone oriented records back around 2010-11 maybe and enjoyed them, but I was very surprised in the best possible way when “Music for Private Ensemble” came out. It felt like quite a leap from your former albums. Like you were communicating or expressing yourself much more clearly and honest.

Does that make sense to you? And if so, can you maybe tell a bit about that process of searching and finding?

SM: “Yes, I needed to do a lot of ruminating to get to that point. Well, to be clear, first I needed to do a lot of experimenting. Thus, why I published so many small releases (around 30) in 2007-2010. Each album was an experiment, all building and learning from the last. None of those are any good, really. Then, in 2010 I moved to Los Angeles and took a break from music for a few months. Instead spending wild nights with my new roommates, not worrying much about anything at all. It was during this hiatus when I decided to start Recital, my record label – which is probably the best decision I’ve ever made.

My interests in sound-art and chamber music had really flowered by 2011. I needed to move on from my ambient/electronic sounds. Currently, exploring new ideas, especially conceptual ideas, is exhausting and time-consuming. Though, this was before that mentality clasped ahold. At this point a new move had been bottled up for some time, and the carbonated “Private” and “Public Ensemble” exploded easily.”

PJ: Where does a new piece of music start for you? Is it the sound or feel of a certain texture that gets you going, a specific instrumentation, specific musicians, an emotion, a more philosophical approach?

SM: “It is a place; a presentation of a place. I start with a consideration of what it is for (a performance or commission) or where it is going (album format). This never used to be the case: it used to be the opposite of this, entirely thrown together layer by layer from a sound or texture I like. Now it is not that way. I sometimes fear that I’ve lost the ability to just improvise a recording, as now everything needs a purpose. I figure I am young enough to be able to try everything and lapse again and again, I hope.”

PJ: Could you maybe describe the journey of a piece – from the first idea to finished recording? Do you have established work routines? How is your workflow and what are your tools?

SM: “I will use the piece “Portraits of Friars” as an example. The piece was premiered as part of Edition Festival in Stockholm at the beginning of 2018. The piece was commissioned by John Chantler, who runs the festival. He told me I had a lot of players at my disposal, so I could dream up nearly anything. It ended up being written for 10 performers.

I love the Blackfriars pub in London. There are as you may expect portraits of friars and clergymen all over the pub walls. I have many calm and beautiful memories there, so I decided to turn it into something audible. This was the place of the piece.

The piece is courtly and tonal, with bizarre text splashed on-top. Etched metals with biblical imagery… nooks and crannies to safely sink in… a fireplace. The influx of rambunctious humans and subverted thoughts set in such sweetly fake surroundings. Beautiful.

In the piece, each player has a page of text elements to recite, and each player has ten composed phrases to cycle through at their own pace, the texts have nearly nothing to do with the pub, but more with the place I was at mentally while in London and shortly afterwards. I wrote all of the text while on a cruise ship with my sister.

The real direction I give is to start with only text recitation and to slowly over-cross into playing music for the course of 15 minutes. The words and texts shuffle randomly within one another. The final 10 minutes are purely musical.

I permit a lot of freedom to the players in my pieces, meaning they can choose their favorite phrases (textually and musically). I don’t like the idea of making a performer play something they don’t like. The players were great, very talented. We did about two hours of practice, then a few hours later the piece was performed at the festival.

It was recorded with stereo room microphones, not the best recording due to the nature of the event. I tried to EQ it and process it to sound better, but I could only do so much. It would be nice to re-record it in a studio one day, although admittedly, fidelity does not matter so much to me (in these contexts). The piece was longer than 25 minutes, entailing that it be placed on a CD, released within a book I published called Saccharine Scores, as opposed to an LP which would have been more successful, perhaps.”

PJ: I sense that your composition work is happening as much after the recording sessions as before. Is this true and if so, what does this approach bring?

SM: “On my albums “Music for Public Ensemble” and “Music for Private Ensemble” it was belabored work. Excruciating editing. I have not done that since. I have worked exclusively on compositions/commissions. I think I will go back to “frame-fucking” (as they call it in post-production) my pieces again, but not for a while.”

PJ: Do you hear the music in your head, before writing and recording?

SM: “I don’t hear it in my head, I paint with one element at a time. I choose carefully and love and hate the surprise of hearing it fused together.”

PJ: I know composers who prefer to only write music for people they know intimately, and some who love the thought of writing a piece that in theory could be played by everyone (capable).

I am interested to know if you write a piece with a specific performer in mind (his/her personality, abilities, tone etc) or rather write for a specific instrument like “a vibraphone”.

Do you think of a commissioned piece as a one off, or something to revisit by yourself or other performers?

SM: “My pieces could be performed and interpreted by anyone that is interested. There is no exclusivity. In fact, I love the idea of that variation in presentation and digestion. I always want someone to bring their character into the work, and I usually leave open windows in scores for that purpose.

I have written for specific instruments. Last year I wrote a solo vibraphone piece for American percussionist Jackson Graham, called “Violet Fat”. Along with “Folded Rose”, a solo piano piece commissioned by Michael Vincent Waller. In both pieces I have the performers use their voice, humming and singing softly. Generating a proximity or a second dimension to the fragile solos. I hope to do more of this work.”

PJ: What are you working on this spring?

SM: “I am finishing a new LP of mine called “Puck”, which I have been working on for a year. It is a single work stretched over two sides. In addition to juggling the rainbow of Recital tendrils, I hope to learn to read German.”