In conversation with BUKHAR – on the role of cultural practitioners in solidarity with global struggles

By Amalia Al-Habahbeh, photos by BUKHAR

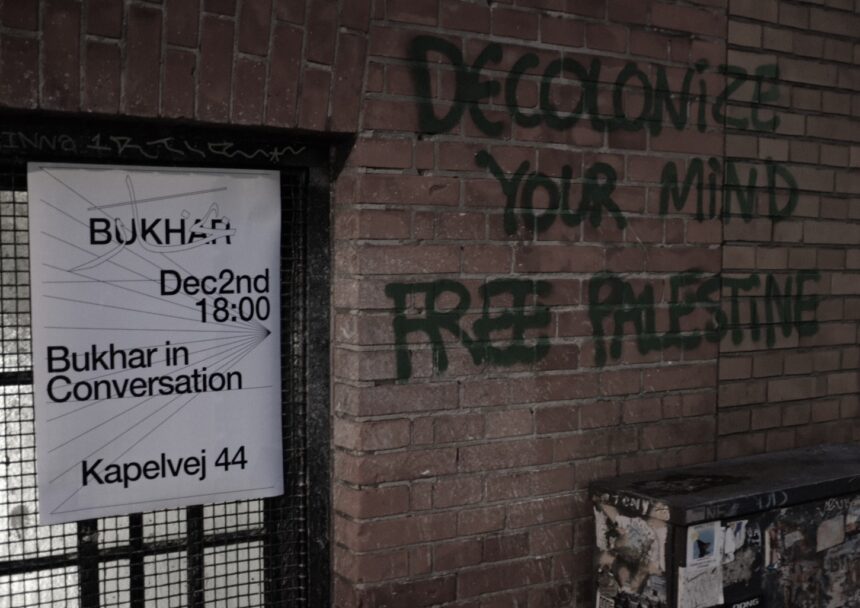

On December 2, BUKHAR held the event “Bukhar in conversation” at Kapelvejens Medborgerhus. The event featured a panel discussion on how cultural institutions can show solidarity with global struggles. The panel discussion was moderated by Yasmina from BUKHAR and included local DJ Nah Care, Nairobi-based Izzo and myself in the panel, followed by a workshop facilitated by Rosa Lois Balle Yahya from Another Life.

The DJ collective BUKHAR (بخار) consists of Yasmina, KUCHULU and Muskila and has in its 2-year lifespan organised exciting and unique events and parties primarily at Basement as well as Baggen. They have challenged the Copenhagen club scene by hosting some of the best curated Southwest Asia & North African (SWANA, previously known as Middle East & North Africa) queer events with music from international acts like DJ Plead, Deena Abdelwahed, Sarra Wild and Copenhagen favourites Kawun, Suzie The Cockroach and of course their own DJ-aliases.

Why do we need events like this?

Most people with a sense of empathy are severely impacted by the live-streamed, US-backed Israeli genocide in Gaza, especially the SWANA community and other marginalized people. For us living in the Global North, the silent complicity and racist double morale of the political and cultural institutions priding themselves with diversity and inclusivity, while the situation in Palestine (and beyond) only worsens, is very hard to bear witness to. In most cultures, celebrations in times where thousands of people haven’t yet been buried, are inappropriate. So an event like this is a welcomed framework to allow our community to meet outside the dance floor and have these conversations on how we as cultural practitioners can engage in solidarity with each other in the best possible way. This is especially important now, as we are seeing alarming censorship and cancellations of artists, venues, and cultural practitioners who are speaking out against the genocide.

An example is the controversy around the popular German music platform HÖR who have been censuring artists for wearing t-shirts and scarves with text in Arabic (including at their pop-up event in Copenhagen last year), or a map of Palestine, something that has led to widespread boycotts and numerous artists removing their sets from the HÖR Youtube channel. This raised important questions within the communities about what exactly is the role of music platforms in global struggles, and how one can show solidarity (if we even should).

Bukhar’s event started out by Izzo setting the stage with a presentation under the headline “Orchestrating for the masses: towards a post-capitalist musical solidarity”. Izzo is a music archivist and researcher based in Nairobi, who focus on the socio, economic and political dynamic that shape the marginalised and alternative contemporary cultural landscapes, whether through Al Rassa collective, Maryud FM, or the soon to be launched digital media platform, Mojiz Alneel, which explores socio-politics in Sudan and the surrounding regions.

“I’m from Khartoum, a city that is about to disappear as a result of local and regional political powers in conflict. Historically, we’ve been the centre of many ideological struggles; pan-Arabism, pan-Africanism, pan-Islamism. Some of these struggles were forced onto us as a result of the institutional leanings of the political powers, and some are a result of being people’s people. But all the conflicts have actively reflected on all types of music, folklore, regulated, and underground”, Izzo starts out. Sudan has a long history of solidarity with the Palestinian cause, for example by hosting the Arab Leagues’ summit in 1967 where the nations agreed to ‘the three no’s’: no peace-, no recognition-, and no negotiations with Israel.

Historically, solidarity through music goes way back. A wide-known example of this, as pointed out by Izzo, is the American superstar song “We Are The World”, released in 1985 to end world hunger. This song became the manifesto of the cliché duality of solidarity – charity signaling the US -Global North propaganda machine a the hierarchy of “the good” charity givers and “the poor” receivers.

Despite its monumental success in raising over $75 million to combat hunger in Africa, its impact falls under scrutiny due to its inability to prevent a series of coups and assassinations that unfolded as a direct consequence of the same propaganda during the song’s release. “This poses an important question: Is this the solidarity we aim for? And why isn’t a grand initiative like this in line with such a heavy title and deed? And most importantly, who are the “We” in the title? The notion of solidarity constitutes an Us/We versus Them, an Us that is recognized and defined by common goodness, collective values, and struggles, and a Them, that solidarity is needed against, as they pose a threat in shape or another for Us”, says Izzo.

“Solidarity is empathy in action, it goes beyond a singular cause and for our salvation.”

Izzo

He continues to explain that we need collective action towards sustainable, active, and revolutionary solidarity, by moving towards true internationalism and post self-centered institutions. This should be done by recognizing our common struggles beyond borders and without appealing to the powers that are invested in our exploitation, because music doesn’t recognize borders, languages, and power statuses. “Solidarity is empathy in action, it goes beyond a singular cause and for our salvation. It is a reflection of a genuine investment in togetherness, towards a community that is exclusively void of “Them”, where “Us” is all that we know and we work for”, Izzo finishes the powerful introduction off and sets the stage for the panel debate.

Should music platforms show solidarity with global struggles?

In the panel, besides Izzo and myself, is DJ NAH CARE, a prominent figure in the Copenhagen club scene, who intersects activism and music by creating spaces for the LBGTQIA+ and marginalised communities by uplifting and amplifying queer and BIPOC individuals through his club concept Club Versatile & MISS THING and his DJ residency at Endurance Cph, amongst others.

Yasmina kicks off the panel by asking the very important question of whether we should even expect different music platforms to come out with statements of solidarity or react to different global events?

Here, both NAH CARE and I pointed out that we expect statements from platforms that claim to represent marginalised communities, or which values and identity are centered around supporting underrepresented voices, and to a lesser degree big platforms, such as Spotify, even though they selectively support certain struggles, such as Ukraine. For me personally, living in Tromsø, a twin city of Gaza City, I anticipated the cultural institutions in my town to give clear statements in support of our twin city. And here, I think that the international festivals have a special responsibility to not only celebrate and capitalise on our culture but also stand in stark solidarity when our people are being annihilated and our culture is being erased.

Yasmina continues by asking, what we think about the difference between what people were asking for and what was happening locally. For example, in Gaza, people were asking for a strike and pointed out that they want political pressure, not fundraisers, but instead many were organizing fundraising parties like Rave for Palestine or initiatives like Artists Against Apartheid.

I think it is problematic when such initiatives do not center the voices of Palestinians. It risks reproducing a hegemonic mentality of “I know better what the people need and my money can fix it all”. It’s important to note that money are important and what is needed in some, if not many cases, but this should always be approached by partnering with local initiatives in the area and on their conditions. If not, it can quickly become a charity or white saviour mentality, where we in the Global North clean our conscience but without doing the actual work towards liberation.

Izzo adds that a lot of solidarity in the music scene, even the industry itself, is very performative because the historical precedents of musical solidarity from the Global North essentially are performative and reactionary. It’s not invested in the long-term strategic plight of freedom for the people but is often a response to a certain event. This is also good for the music industry because everyone will feel good about themselves when consuming this type of media, feel good when buying the music and the merch to help Haiti, for example, but it doesn’t help Haiti in the long run – it will only serve as a Band-Aid.

NAH CARE agrees and asks the difficult question of how we, as music platforms, party hosts or clubs should show long-term solidarity. Is it enough to fundraise and have a flag in the door? How and if should we bring the conversation about genocide, war, and ethnic cleansing into the club scene where people come to find refuge from the world on the dance floor and are often intoxicated? Another thing he points out is that many are now looking to book significantly more Palestinian DJs compared to before the onset of the current ethnic cleansing campaign in Palestine following the October 7th attack, and Ukrainian a while back, maybe to tick a box or ride the wave of attention on a topic. Of course people should book them, but why only now? What about the past 75 years, and in the future when Palestine is not trending anymore? Again, when support is based on singular events it risks being merely performative. And is it really enough?

“People are forgetting that many of the things we take for granted today, such as queer rights, club culture, etc., were achieved by people rising up and confronting the establishment.”

Many of us are learning by doing, so having these conversations are, in my opinion, an important first step because we can’t have all the answers to begin with. For many people it is the first time being confronted with these challenges, so we need to continue having these conversations. And here I am thinking especially in the electronic music scene which historically has been a space for marginalised people. It is ignorant to take this out of the equation and think that music and politics can be separated. These cultural scenes, like hip-hop and Pride, have been hijacked by people that don’t know or care about the origins and political nature of those communities. People are forgetting that many of the things we might take for granted today, such as queer rights, club culture, etc., where achieved by people rising up and confronting the establishment and taking actual risks.

Izzo adds that music made by people expressing their struggles is revolutionary music, and that it reaches these privileged places through the commercialization machine, but when it is marketed to the Global North, it is completely stripped of all its context. He stresses the responsibility of us who work with this music to remind people of the gritty reality of where the music comes from. House music, for example, was formed by black working-class queer people in the grittiest Chicago warehouses where people gathered on the liberated dancefloors in a country that does not recognise black people as people. However, this history is often erased and today the commercialization of the genre often reduce it to just a vibe, TikTok-, or ad music.

Performative or operational solidarity?

Yasmina asks if social media has made it easy for individuals and institutions to formalise their solidarity through statements. But does a statement constitute an act of solidarity or does the lack of a statement suggest a refusal of solidarity? This becomes especially problematic when the statements are issued as a reaction, but not in direct relation with the concerned political struggle. So how do we avoid our statements becoming a reaction to a reaction? Is there any solid work being done behind these statements on social media, particularly in the clubs that boast of safer spaces politics and prioritising marginalised communities? Or is it just a reaction of “the good guys” against “the bad guys” so they don’t get cancelled?

Izzo answers that much of the inclusivity coding of People of Color (POC) clubs are well-meant and important but it might take us back a few steps in the long run, when it is the bare minimum and is not followed up by additional work. It might even be a marketing strategy to get POC and marginalised communities to come to these places despite no work being done for these communities. Statements does not do anything and actual operational solidarity is a difficult process that will take a lot of trial and error for us to learn from each other – and one might even risk one’s financial stability. To add to Izzo’s point, I bring forward an example of the Berlin venue Oyoun who have lost their public funding and will have to close down, after they hosted an evening of “mourning and hope” by the organisation “Jewish Voice for a Just Peace in the Middle East”.

On the 8th of January 2024, the Culture Committee of the Berlin Senate introduced an “anti-discrimination” clause. It requires receivers of public cultural funding to adhere to the controversial IHRA definition of antisemitism which conflates criticism of the state of Israel with antisemitism. Critiques of the clause say it will be used to silence and exclude those critical of Israel and the German government’s war policy through McCarthyistic policies that suppress artistic freedom and freedom of expression.

NAH CARE gives an example of where a process of issuing a statement led to valuable reflections, “I was talking to someone from Trauma Bar in Berlin, who wanted to come forward with a statement, but after he asked them (Trauma bar staff) why they wanted to do that, they hadn’t really thought of that and were more or less just jumping on a trend. But it sparked discussions and in the end they came out with a statement saying that as a music space hosting Palestinian artists, they felt they needed to show solidarity, since you in Germany can get arrested for just wearing a kuffiyeh (Palestinian scarf) or for simply asking for an end to the genocide”. They further offered lawyers to individuals who needed legal advice as a result of this repression, so it serves as a good example of a venue doing the work that should be behind any statement like these.

Solidarity or partnership?

Solidarity implies hierarchy – usually the global North is in solidarity with the “weaker” group in the global South, making solidarity a marketplace that some enjoy more than others. Do you think we can move more towards partnerships and if so, how can we achieve partnership within our work in the music industry?, Yasmina asks us.

Izzo answers that the act of solidarity has become a commodity and great marketing for record labels, music blogs, and artists alike. Real solidarity or partnership is difficult, but it is the only way to liberation given the concentration of power. It might be difficult for artists to go against giant platforms like Spotify and Universal since many may need to align with them in order to survive in this capitalist world we are living in. But our collective power is bigger than theirs, and despite their immense financial power, they have no other investment in us besides the profits they reek from our labour. We need to have these conversations and continue working together towards our common goals.

“Music is supposed to be a true expression of a person and not to be consumed.”

Izzo

The debate was followed by a question from the audience, asking how we as consumers can rewire ourselves to demand better things from artists and platforms.

Izzo answers that one of the most interesting commodifications of our time is the commodification of music. Music is supposed to be a true expression of a person and not to be consumed. But even if the artists want to sell, often they need to modify their art for the platforms to better push their content, and smaller artists do not make much money from these platforms anyways. What we should be focusing on is how we can provide alternative ways to get artists the money.

To add to that, I brought up the challenges that followed the call to strike in solidarity with Palestine in October. Artists do not have strike funds, sick leave or other benefits, so for a lot of people it was a very hard decision to make. I also think that we need to collectively start talking about how we can challenge the big commercial platforms and institutions, as we are seeing these platforms increasingly centralize money and power. Of course we should engage with individual artists and smaller platforms, but in the grand scheme we should maybe start demanding things from the big platforms like Spotify, HÖR, and Boiler Room because they are already dictating what is popular. NAH CARE adds that these platforms are so unreachable, but maybe that is where our collective power could be a force to start making some demands as “consumers”.

The panel debate was about to end at Kapelvejens Medborgerhus. I felt energised to talk more, but I am sure the points made so far has given attendees a lot to think about. What is essentially needed is genuine, long-term engagement, with an understanding of the historical contexts, while working towards meaningful solidarity and partnership in the music industry and this should be achieved through our collective power. This way, we can move towards real solidarity with the people of Palestine, Sudan, Congo, Kurdistan, Haiti among others.

Editor’s note: The article is expressive of the writer’s personal opinions.