MINU Festival 2024 – Expanding music between institutions and communities

By Macon Holt

MINU is an annual festival for what it terms “expanded music”. That is music that simultaneously rejects the necessity of the conventions of the “Western musical tradition” and the commitment to vanguardist or inscent progressivism of a label like Avant Grade while pursuing new ways of music making. However, in keeping a notion of inclusivity in the idea of “expanded music” both are still present to some extent. An example of what could be termed ‘expanded music’ along the lines of the festival’s own conception included Dalin Waldo’s multi-media/performance-lecture/interview/auction on the limits of the Ableton interface to make music appropriate to the present moment of very late capitalism, postcolonial violence and capacities of digital life to make identity something inherently and desirably unstable. Or the play of manners/food fight performed by the composer’s collective Current Resonance that amplified the masculine fragility at the heart of the normative conception of the composer-as-genius to the point of absurd implosion.

When I reviewed MINU festival in 2023, I started with a caveat, almost an apology for my inability to attend everything. This year, I wanted to integrate the obstacles caused by my institutional responsibilities to Copenhagen Business School into how I communicate what I understood of the festival because of the central role that “institutional critique” seemed to play in many concerts. For those not familiar, institutional critique is a contemporary art movement concerned with the institutionalised conditions in which art is produced today as it relates to the idea that art should somehow be able to comment on society and life from an outside perspective. In a kind of fourth-wall-breaking gesture, these artists point to the funding structures, formal conventions, critical conventions and cultural narratives of artistic value to raise questions for the audience about what exactly they are experiencing or reproducing by consuming art. Often such work is made by artists working within the structures that they criticise.

Expanded music simultaneously rejects the necessity of the conventions of the “Western musical tradition” and the commitment to vanguardist or inscent progressivism of a label like Avant Grade while pursuing new ways of music making.

I bring this up because implicit in the notion of expanded music itself is a critique of what music is institutionally delimited as. Yet the community of people most central to putting this festival together came together through the institutional structures that enforce this delimitation. This is the paradox of critique that some people misunderstand as hypocrisy. The means of meaningfully addressing what is wrong with how the world is and or expressing our displeasure with this condition are largely controlled by institutions that perpetuate what we consider to be wrong with the world.

Eclipse

The tensions of these power imbalances became apparent in the opening event, Eclipse at Ku.be, which got its title from one of “The Tzitzimime Trilogy” (2021–2023) of short films by Mexico-based artist Naomi Rincón-Gallardo, which made up the middle of the program. In the context of the festival, these works were among the best in articulating the refusal of the problem of institutions. Perhaps because these artists never believed the institution was ever meant for them.

The films were bookended by two pieces by Navajo composer Raven Chacon. Chacon’s first piece, American Ledger No. 1 (2018), saw an ensemble of musicians from the local new music scene and beyond perform a graphic score fixed to the wall in front of them while conducted by one of the festival’s founders Dylan Richards. “American Ledger No. 1” is a retelling of the founding of the United States of America that combines musical representation and actualised gestures that refer to the events it depicts, including chopping wood, the harsh whine of police whistles, throwing coins into a bucket and most arrestingly of all the lighting of a match before a microphone before blowing it out. Treaties are negotiated and broken, the law is weaponised in service of colonisers, money overtakes all other forms of value and the spark of other forms of living is extinguished. However, the repeat marks in the score hint at different temporality that relativises this process. As if, from Chacon’s perspective, this history of the United States that the colonisers laude all so highly is part of a much larger unfolding and will, itself, dissipate. Chacon’s political critique is held simultaneously with a cosmology that both denounces the genocidal injustices his people have suffered and points out the fatal hubris of the violent systems that have inflicted it. The materialist myths of control and property that the United States and states as such are founded on are fragile things that will crumble as something new emerges.

Naomi Rincón-Gallardo’s films explored a different but related cosmology. The Tzitzimime Trilogy takes its name from the skeletal female deities of Aztec mythology who served as protectors and a source of human life and fertility. The films drew on these figures and represented them and others through a trash-queer-techno-drag stylization. This style folded in contemporary Mexico’s position as a site of extraction and expropriation in globalised capitalism with the tension this Indigenous cosmology exists in relation to the repressive conception of sexuality at the core of the colonial capitalist project. Integrating punk, metal and electronics, the spoken word narration provided a chilling narration of the end times in which we live from the perspective of a civilisation that has already witnessed its own almost complete annihilation. This far-from-unique, in global terms, perspective allows for an irreverence about existing at this moment of ecological and social precarity. A perspective remains unavailable to many still committed to the reproduction of the world as it is with all the violence that entails. Free of that commitment, however as one deity invites us, we can be “ecstatic at the edge of the abyss”.

We were then led out to the foyer and invited to take an instrument to participate in a performance of Chacon’s …lahgo adil’i dine doo yeehosinilgii yidaaghi (2004), which translates from Navajo as “acting strangely/differently in the company of strangers”. Richards conducted this motley crew of slightly embarrassed but overall curious mostly-Europeans through fifteen pages of graphic notations, each producing something distinct if not coherent. But the musical object, its beauty, its comprehensibility was never the artwork. Rather it was the act and the relationship between the Chacon and the predominantly white performers as we were made to attempt to comprehend his demands on us.

…their loyalty and responsibility was neither to conform to nor resist this institution on its terms but to articulate their desires through the means available even if they cannot be realised in the present.

In both of these artists’ works their relationships with institutions as the structural means for disseminating the power of the state, capital and their ideological underpinning were far from what could be called consensual. But they weren’t naïve about the nature of this power imbalance and the limitations this placed on the effectiveness of their critique. Thus their loyalty and responsibility was neither to conform to nor resist this institution on its terms but to articulate their desires through the means available even if they cannot be realised in the present.

(I Love You) for Instrumental Reasons

The context of the opening night’s concerts heightened the internal tensions in composer/performer Michael Hope’s debut concert graduating from the Royal Danish Music Conservatory the following night. (I Love You) for Instrumental Reasons was an incredibly high-risk piece that pushed the alienation techniques of new music composition, epic theatre and its descendants in the world of stand-up comedy, like Stewart Lee, to a limit.

However, in the context of metamodern art practice, Hope’s blurring of irony and sincerity did land on the side of producing a genuine moment of connection in an incredibly innovative way. The conceit of the piece is that one need not “expand music” as shown in the opening which featured a synth drone and sparse piano referring to the institutionally dominant style of Scandinavian minimalism. However, it is repeatedly talked over by Hope, who comes on stage to attempt to justify why this performance will just be this. Eventually, this unravels as a new music ensemble enters the stage to let Hope rework some old compositions of his that sound exactly like the kind of abstract complicated cacophony that is normally called “new music”. This is made to compete with a conversation in the corner of barnyard animals having a long, inane but animated conversation about the virtues of different variants of Diet Coke transcribed from an apparently real podcast. While in the opposite corner, the chess game between the Knight and Death from The Seventh Seal plays out without comment. As Hope’s frustration with the ensemble’s inability to realise his vision grows the tableau breaks. The composer went down to his shirt sleeves and the barnyard animals are set to work as he attempts to sell his compositional genius on the financial markets with frantic phone calls and hostile accusations that his fellow performers are not committed enough. When this fails to gain him the adoration he feels he’s owed in return for selling out to institutional demands the other side of his “devotion” to craft is revealed.

Donning the black cap and coat of a musical fascist paired with fishnets and high-heeled boots, Hope turns his ire on the audience for not appreciating music correctly and expecting the wrong things from him. Ironically, for expecting exactly the kind of musical experience he is giving. Calling his parents on stage to correct his performers playing, who now all wear a mask of his face, Hope marches back and forth across the stage outlining the limitations of what should be considered music. He then ran up onto the balcony to call a stop to the attempts to realise his work taking place on stage. And confronts the audience directly about what he perceives as their unjustifiable refusal to “love him”. Asking individuals in the crowd if they love him and simply not taking yes for an answer. Frustrated that nothing has worked in the way he imagined that it should have so far, he demands the audience follow him down to the stage to sort this out one by one. He starts to chat with one person in a chair as the atmosphere is still tense with the reverent silence of concert etiquette but the unamplified conversation meant that, eventually, the inability to participate in the performance gave way to chatter amongst the crowd. Then, without being noticed, Hope slipped away and friends, colleagues and strangers found themselves chatting without direction. After a few minutes of this, I heard a small smattering of applause in the corner as the chess game between Death and the Knight was finally over.

The piece’s final gesture, Hope’s disappearance into the crowd, should not be read as deferring to the people in some kind of trivial affirmation of democracy in art. It is rather a way to highlight the complex ethical relationships that exist in institutionalised aesthetic experiences.

Hope’s work presented an intensely personal admission, from the persona of an experimental composer, of institutionalisation. This means not only experiencing the pressure of the demands of the institution to perform a certain way to gain its approval but also that it has structured the character of Hope’s desire such that he believes this is what he wants. But it is not. Hence the shame-filled refusal of the conservative instruction and the fascist fervour with which it is felt. The piece’s final gesture, Hope’s disappearance into the crowd, should not be read as deferring to the people in some kind of trivial affirmation of democracy in art. It is rather a way to highlight the complex ethical relationships that exist in institutionalised aesthetic experiences. In the end, we didn’t need him but we could consent to let him bring us together.

…

Two days passed when teaching students at the business school sapped almost all the energy I would need to participate. I caught Endolphins by Berlin-based sound artist Hanne Lippard at Platform Bunker. This multi-channel spoken-word installation played on the emergent homophony between endorphins and dolphins and other phrases that can come from repetition. The piece neatly articulated a poetic narrative of alienated digital communication and individualised erotics through absurdist minimal spoken word.

it was easy to see how Lippard was able to make it convincing that so much individual access to the world had produced a form of alienation.

I awoke the following morning to footage of one performance I missed on the festival’s Instagram Story of pianist, Rob Durnin, gingerly trying to turn the page on a manuscript before stepping away from the flames that engulfed it during the previous night’s performance of Annea Lockwood’s, Piano Burning (1968). High-end microphones surrounded the burning instrument to catch all the crackles and twangs.

“Piano Burning” is an iconic piece of institutional critique. It takes an almost sacred and material expensive object of the European musical tradition and reduces it to ashes and burnt metal. Its historical origin in the anti-institutional cultural uprisings of ’68 positions this piece as a canonical example of questioning the cannon. The kind of thing that is written about in academic histories of contemporary music and documented in black-white photographs and hissy tape recordings that obscure what is burning piano and what is static. Now, in 2024, in the culture that for better and worse has emerged in the wake of that period of rebellion, I can catch up on this artistic invitation a few hours later as a clip on social media from my bed. Thinking back to Endorphins, it was easy to see how Lippard was able to make it convincing that so much individual access to the world had produced a form of alienation.

The Bakery

I arrived late to 5e for the durational performance of Niels Lynne Løkkegaard’s The Bakery (developed in collaborations with composer/performers Dylan Richards and Niklas Brandenhof) and found Løkkegaard and composer James Black sitting on the floor before a small crowd, gently caressing their saxophones which lay upon slices of white bread with pastry spatulas. At a particular moment, Løkkegaard looked up from this new ritual to engage Black in conversation about their relationship to each other in the expanded music scene and how their complicated relationships to this instrument and their families informed their approach to their practice. The Bakery was in an exploded rondo form. A rondo starts from a primary theme, the ritornello. It then alternates between this passage and various episodic segments. Throughout the day, whether it was “Waffle time”, an exploration of the anglophone trouble in pronouncing the Danish “soft d” or softening for the saxophone, each section was divided by a ritornello during which Løkkegaard and the other performers in aprons would play a tape from a recorder attached to their belts containing a rendition of “Duo des fleurs” from the opera, Lakmé by Léo Delibes.

What came out was a conversation about the ambition to eschew the limited notion of ambition institutionally recognised success that had come to dominate contemporary music. With this came a desire to produce a space through musical means to facilitate a more open and vulnerable kind of experience and opportunity to form a community.

It was in the ritornello that followed the saxophone softening that Richards approached me to see if I would be a willing critic to participate in the salon that was to follow. I agreed and Brandenhof handed me a coffee. I took my seat at the round table that had been constructed in the seating area and began inviting the three performers to reflect on their experience composing and delivering the piece as a tape recorder on the table whirred documenting the exchange. What came out was a conversation about the ambition to eschew the limited notion of ambition institutionally recognised success that had come to dominate contemporary music. With this came a desire to produce a space through musical means to facilitate a more open and vulnerable kind of experience and opportunity to form a community. In the negative, this conversation revealed one of the most enduring institutional scares many artists can relate to, namely the internalisation of one’s artistic value being tied to the whimsical decision of institutions in how they allocate resources.

Thinking back to Hope’s piece, the anxiety of his persona becomes all the more clear. If we do not love him and designate him as a genius so as to allow resources to come his way, can he even be a person, let alone a composer? Løkkegaard’s work was an attempt to resist that logic. And while the impact of that resistance may be quite localised, to hear Brandenhof talk about the dissipation of his pre-concert excitement/anxiety into something more akin to feeling like he was part of a community in this piece through his service to others, the impact was undeniably real.

INTERVALL & Materize

Later that day the program continued at Dansekapellet, a contemporary dance venue in Copenhagen’s Nordvest neighbourhood with two performances. The first was INTERVALL composed and performed by the percussion group Pinquins in collaboration with choreographer Kjersti Alm Eriksen. The ensemble operated a large wooden scaffold from its wings through strings and pulleys and assorted percussion and metalware scattered on the floor. With incredible temporal precision, the performers would release objects from this contraption, many of which would then dangle in space and make sounds through the chaotic process of air currents once released. These releases often came with the sensation that once done they could not simply be “undone”. While held in the tension of waiting the objects in the scaffold were for the most part silent and concealed, unable to affect the audience in their individuality beyond how they contributed to the scaffold’s totality. Once released they became affective, shimmering, swaying and rattling. But they were also able to be affected, as they were continually influenced by every other action of the performers and the other components. It is this space between choreography/composition and any kind of realisation that is the INTERVALL in question. As I thought through INTERVALL of the gap between the institutional fantasies and the lived actualities of those real people who comprise them, the importance of understanding the impossibility of ever completely closing this separation became all the clearer. But so too did the interpenetration of the fantasy and the actual.

Materize from Copenhagen-based composer and new media artist Sól Ey, approached a similar gap, namely that between concept and execution. and her ensemble (including the piece’s choreographer Alvilda Faber Striim) were scattered amongst the audience, set apart by the almost satirically cyborg/intrusive wearable tech instrument of Ey’s design, the Hreyfð. The performers stared at individual audience members, approaching them for a time, and mimicking their movements. The varying levels of anxiety that this induced in audience members dictated how fruitful the improvisatory feedback was. As the dancers discovered the necessary relations between each other and their own suits, the Hreyfðs began to chirp. At first, these seemed random but eventually, as the performers came together and their movements came closer to unison the chirping feedback became a pulsing wave and the lights built into the Hreyfðs sparkled too, heightening the crescendo of the piece’s structure.

Materize is an effective experience but when considered with its own description in the program. It is difficult to say that the tech on display in the Hreyfð or the choice to execute the piece in an alienating choreographic style reminiscent of mid-twentieth century postmodern dance (which is really a form of high-modernism despite the name) are the vehicles through which to attempt a renegotiation with technical being through the ethics of care. In short, that gap between concept and realisation, which can never be fully closed, felt still too large. At times it felt like witnessing a necessary technical exercise that could one day lead to the realisation of something conceptual. But for now, institutional hoops have to be jumped through.

POWER relations

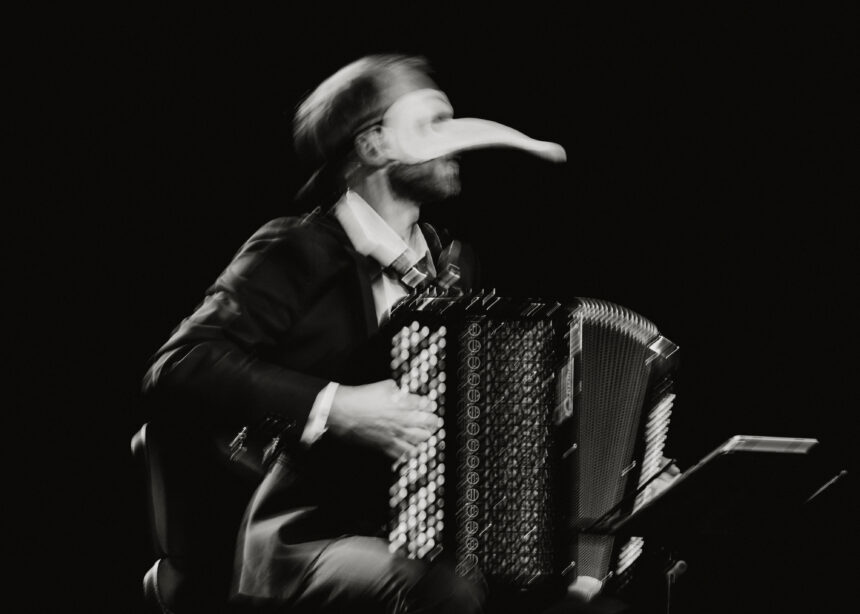

Missing some concerts at Mayhem on Saturday night owing to the exhaustion of my own institutional labour, I caught up with the festival on its final day with the afternoon performances by Danish accordion virtuoso and ever-game expanded music performer, Andreas Borregaard, at Dansekapellet.

The suite of works collected under the title POWER Relation comprised four pieces. The first, Henki (2022), from Finnish composer and sound artist Tytti Arola, featured Borregaard playing the accordion under a white sheet catching the projections of, among other things lips and swirling colours, that landed on the screen behind him. The title, Henki translates from Finnish to the English words breath, life, ghost, person, spirit, soul, and atmosphere and the slippage between these concepts is clearly what is at play here given Borregaard’s spectral attire, which would be broken from time to time with the emergence of a leg. Audio playback is largely made up of the breath sounds accompanied by Borregaard’s playing. These were at once intimately excited but also eerily similar to the respiration of the unseen accordion. In Arola, composition, as the title would suggest, questions about what a person is, what they do, where they are and what might be essential about them are made to hang as endearingly unanswerable.

Relationer (2021) the Danish word for “relations” was made in collaboration between composer, Louise Alenius and Borregaard. This piece ups the tension that inheres in the ambiguity. It opened with the accordion now in full display, lying unfolded over Borregaard’s stomach as he lay seemingly unconscious on the ground. Borregaard then attempted various ways to relate to the accordion and the stool in a number of more or less awkward ways. He discovered new ways to sound the instrument all of which are less convenient or versatile than the conventional hold but brought their own disquieting sonics into the room.

The most unsettling moment came after Borregaard had demonstrated his skill in playing a number of complex figures in the conventional accordion hold. As one would expect, his playing was compelling and immaculate. While playing, he spelt out G-e-n-k-e-n-d mellemrum d-i-t mellemrum m-ø-n-s-t-e-r (recognise your pattern). He then rotated the accordion to play with the opposite hands and struggled to produce a disjointed mess. With this, we get a little peek at the double nature of power as it relates to institutionalisation. Being brought into the classical school lets a person willing to conform realise the most dazzling heights of sanctioned achievement but leaves them vulnerable in the event that this system of coherence disappears. Indeed, our relationships with institutions allow for the realisation of great things according to those institutions’ terms. But doing this requires us to internalise those terms which can render us incapable of finding value beyond them. Who’s pattern was it anyway?

I cannot think of a better summation of millennial middle-class subjectivity in late capitalism

The final piece in the suite from composer, Laura Bowler, and dramaturg, Sam Redway, was POWER play (2024). This short play saw Borregaard as a nervous job applicant dressed in a scruffy suit topped off with an uncanny Zanni mask referring to the servant trickster characters of commedia dell arte. The performance depicted Borregaard’s Zanni being assessed for an employment position by some faceless company, represented by various disembodied, unsympathetic voices that instructed the applicant to perform various tasks on the basis of his inflated CV. Chief among these was his master level of the accordion. This nightmare scenario, which is likely familiar to anyone who has felt underprepared for some kind of life-chance-deciding examination, had Borregaard clownishly and reluctantly try to play the instrument as if he had never encountered it before. Eventually, he broke into song, repeating mantra-like, “I feel something, I don’t know what, something pains and yet excites me” much to the disapproval of the disembodied voices. As a mantra, I cannot think of a better summation of millennial middle-class subjectivity in late capitalism, particularly as it relates to the power institutions have to make or break our identities based on their seemingly arbitrary judgments. Perhaps this is what was actually articulated in this suite.

LSWR

The Festival’s final movement took me back to Ku.be, and featured work from Copenhagen-based composers/performers/programmers/inventors, Gianluca Elia & Lorenzo Colocci’s immersive multi-media music theatre piece LSWR (2024). Though I haven’t managed to find a convincing expansion for its acronym title, this was a masterpiece of post-institutional critique, in part, directed at MINU itself. Through the performative deconstruction of the festival’s formal and conceptual foundations, LSWR sought to destabilise the subject positions of the audience as the appreciators of musical expansion by inducing a level of anxiety perfectly dosed to allow those of us in the work to notice our reactions, discomforts and excitements without the need to distance ourselves our experience. It did this by utilising on the one hand a generous but cutting style of self-aware humour and, more unsettlingly, deploying the means by which contemporary social media companies provide users with the illusion of agency.

Posters around the venue instructed the audience to scan two QR codes that let them access a chat room designed for the performance. This was quickly filled with the confused mumbling of people not sure what they had signed up for. Then, huge blocks of text were posted that appeared to be from the LSWR ensemble, which claimed that it was through this interface that we would be guided through the performance. None of this was apparent from the program notes which started out explaining something that sounded vaguely like expanded music before descending into an ordered chaos of Unicode symbols.

As we were led by members of what the message has called the “Insecurity Team” who wore yellow vests, we found a room with a single performer, the only one whose name was parsable in the program, David Sebastian Lopez Restrepo, wearing overalls next to what looked like a live electronics set up before an arrangement of chairs each with what looked like a reduced version of the festival program brochure on them. On closer inspection, the brochures were covered in the glitch aesthetics of unreadable but standardized text chaotically laid out. There was some kind of playback going on or maybe there wasn’t. Memories twist in recalling moments of confusion. As we took our seats Lopez Restrepo approached someone in the front row, apologising he said he needed the chair. He took the chair and put it on the rack before moving on to the next person and repeated it for every chair in the space. About halfway through this, the insecurity team opened the door to lead us out.

The chat was picking up. Every unmuted phone chirped with some kind of garbled speech with each new post. It had turned into shit-posting, and any post authorship, whether or not they were in the crowd or somewhere else unseen, was impossible to know. As we were led through the utility basement, fragments of sounds played from discreet speakers. Looking past the pipes and cables, mannequins and other models were posed in disquieting ways. At the end of the hall, were two person-sized smartphones. One propped up showing what looked like surveillance footage of Lopez Restrepo alternating between cleaning up a room and covering it with toilet paper. The second lay on the ground the screen up and with lines of what looked like scaled-up coke racked on it.

We were led onto a bridge on the second floor with a locked door at the end. From here, we could hear unsettling improvised electronics and strings coming from above. Descending from the railing over the bridge was a ream of paper with what looked like a continuous text on it and we could just catch a glimpse of Lopez Restrepo periodically spilling more and more over. Some people read it. Others grabbed some. On the third floor, we finally saw an ensemble of masked string and electronics players we’d heard on the bridge. There we could see that Lopez Restrepo was ironing passages of text from transfer sheets onto toilet paper. In the control room sat another performer at the desk looking out the window, seemingly narrating and writing in real time the artistic statement for the work that shifted between a lucid critique of cognitive capitalism and garbled art-speak.

LSWR was powerful because it engaged performativity instead of performance. Rather than asking us to consider a representation of the world as it is, it attempted to make the composers’ critical experience of the world into the audience’s reality.

At the door to the next room, a masked member of the insecurity team handed us another pamphlet featuring a washed-out glitch appropriation of the MINU branding. Implicitly hoping for some explanation, I opened it and was confronted with full pages of incomprehensible unicode and my own yearning for some kind of grounding. Lopez Restrepo came out this time in a suite. He took the overdriven microphone and began to describe something of the thesis of the work that was hard to grasp in the moment before declaring that he would now hold an auction for the object of art, a portion of the toilet roll presented on a silver tray. The final bid of 250 kr. came from Brandenhof who had participated in “The Bakery”, and he was made to pay on the spot. With that, the auctioneer left the stage and the lights went out. Wandering around the crowd found a final room with manquined supine on the floor linked up to light-triggers and noise generators and a the rig for a live electronics show that had not taken place. Much like Hope’s piece, LSWR dissipated.

This description cannot do LSWR justice. The piece was at once sincere in its criticality of techno-capitalism, and contemporary art and music’s anaemic response to the condition it produces for life and the labour that sustains cultural production. But it was also playful. By using and abusing the material of the festival that had given this piece a home, it served as a reminder of how MINU itself exists in proximity to the very institutional logic it sought to escape and must be vigilant if it is to retain its position as a platform through which to expand music.

LSWR was powerful because it engaged performativity instead of performance. Rather than asking us to consider a representation of the world as it is, it attempted to make the composers’ critical experience of the world into the audience’s reality. While it could only ever partially achieve this immersion, to the extent that it was achieved, this work was incredibly generative both in terms of reflection upon the lived experience of the multiple crises of the present conditions of capitalist digitality and fostering some kind of fragile sociality in the crowd. I want more art (music or otherwise) to take its role in articulating the present conjuncture this seriously and with so much humour.

A distinct angle that MINU offered up this year, perhaps intentionally or perhaps not, was the damages and capacities created through institutionalisation.

…

MINU 2024 was a welcome and necessarily taxing festival. Filling in some way a void in the Danish scene left by the seeming disappearance of Click Festival and GONG Tomorrow, while charting out a space of experimental and wilfully patient testing music. It attempts to bridge music’s false institutional and discursive separation from art. A distinct angle that MINU offered up this year, perhaps intentionally or perhaps not, was the damages and capacities created through institutionalisation. This would be clear to those who have undergone the disciplinary torturers of becoming a “classical” musician. The intolerance of error, the fidelity to the score as the word of god, and the instrumentalisation of the body in the service of the “sublime” can all create a conflict between the aspiration for admiration and the criticality contained in the discomfort these processes induce. And this is before we see how these values play out at the level of curation and funding.

In making space for expanded music, MINU straddles this conflict by showing what is possible outside of institutionally sanctioned expression through the means of institutional resources and training. Sometimes this is the complex denouncement of what the artist is actually doing, as in Hope’s work, sometimes this is the therapy of The Bakery, the melancholia of POWER Relations, or a playful but searing reconfiguration of reality like LSWR. But in all of these, one can find the possibility of something new emerging.

MINU_festival_for_expanded_music 2024 ran from 26/11 to 01/12. MINU is co-directed by Mikkel Schou [K!ART] and Dylan Richards [Current Resonance]