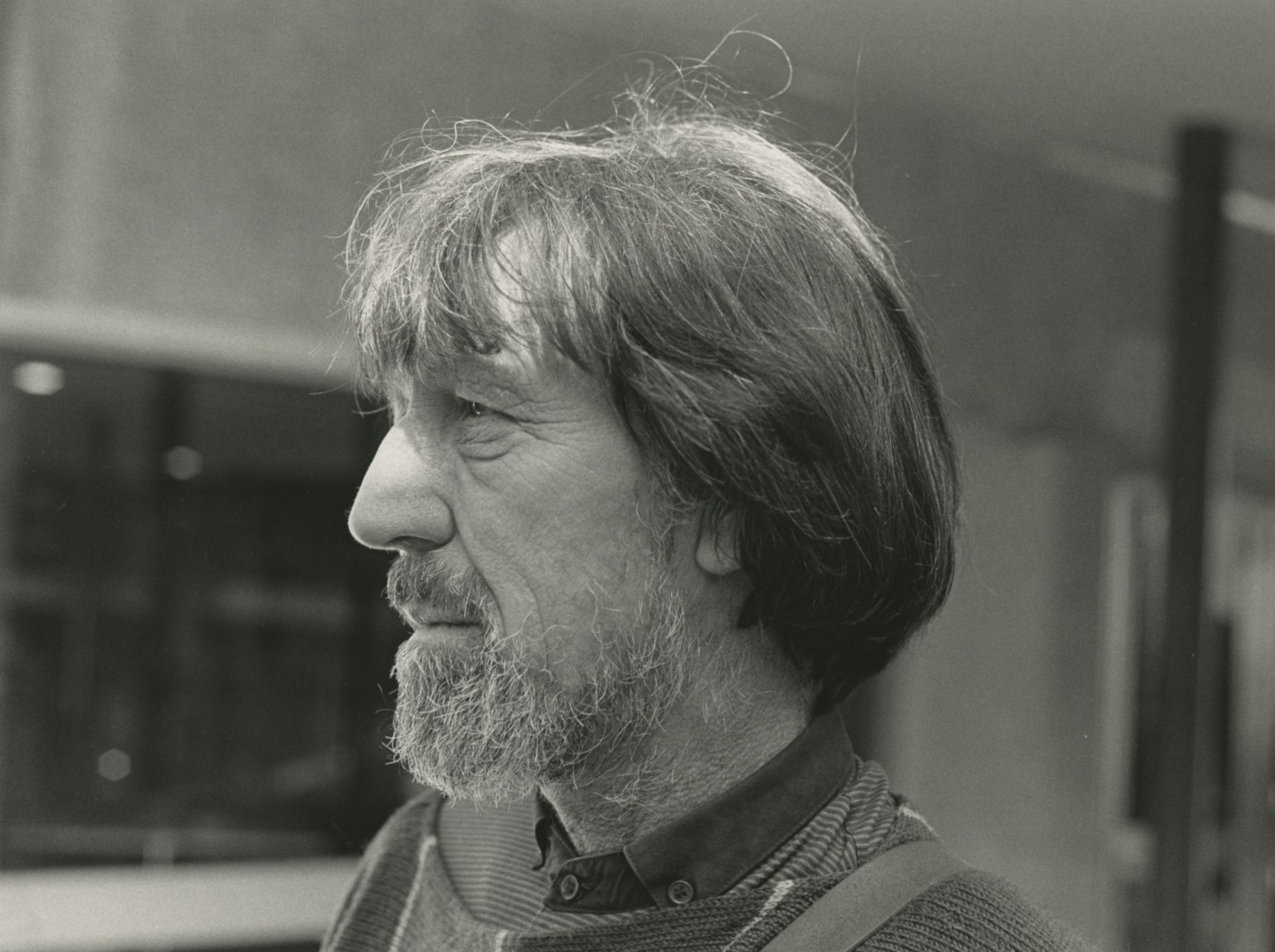

Peter Voss-Knude – “Danish politics are the mother of this record”

Feature/Interview by Macon Holt

“Danish politics are the mother of this record”, Peter Voss-Knude told me in a small cafe around the corner from the Museum of Contemporary Art in Roskilde, where his new exhibition, “The Anti-Terror Album”, manifest both as an exhibition and a record, has just opened. He is of course referring both to recent policies that have seen threats of refugees having whatever valuables they were able to hold on to confiscated by the state; or the recently scrapped plans to house “unwanted” immigrants on a deserted island; and pernicious projects like the infamous ghetto laws. He went on to explain that simply living in Denmark, he feels constantly surrounded by this terrorizing discourse that spreads and amplifies the threat of terrorism. Indeed he sings as much in the lyrics to the funk-pop track “Nasty Fruit (Wake You Up)” from the album showcased in the exhibition as he declares a desire to acknowledge and change “all the embarrassing politics that our nation is a symptom of”. This track, in combination with the record’s opener, “A Racist Nation”, kicks off the narrative of “The Anti-Terror Album”. The first track builds tension with blurry acoustic and synthesized atmospherics in combination with spoken word accounts that offer a lay of the land before being released by a driving beat and heavily distorted, more declarative and less circumspect vocals. Voss-Knude cites the British breakbeat and house group Baby D as a major influence and while that is certainly present throughout the record, and to an extent on the album’s opener, something else seems to happen when dance-oriented music is filtered through political anguish. “A Racist Nation” is a track that tries to grapple with the pain of political disillusionment about a status quo that has, for the most part, been so good to you but at the expense of others. It becomes something of a mission statement. In this way, its distorted vocals and synthesized atmospherics are somewhat reminiscent of a turn of the century Radiohead track like, “Packt Like Sardines In A Crushd Tin Box”. But while the the band’s anti-imperialist sentiments seemed outlandish in the world of June 2001—an apathy they captured with the song’s constant refrain of “I’m a reasonable man, get off my case”—almost 20 years after 9/11, Voss-Knude is looking to build a new consensus to help us escape the weaponization of a politically inflated sense of terror. This is why he adds a conciliatory note to his declaration that Denmark is a racist nation; “I wouldn’t say this to you if it wasn’t completely true”.

The exhibition itself is set up as a listening space with couches and coffee tables covered in the supplementary material and evidence of Voss-Knude’s investigation and exploration of war-on-terror-myth-making. There are two large charcoal murals, the most striking of which is a near-exact copy of the poster for season four of the TV show “Homeland”, which features Claire Danes’ CIA agent as the only face looking towards the camera wearing a flowing and loose-fitting hijab amongst a sea of dehumanized women in burqas. The show has been severely criticised for its incessant depiction of muslims as terrorists. Of course, while the promotional material for the show tries to point to its star’s individuality by depicting her as the lone source of colour surrounded by grey conformity, complete with a brilliant scarlet headscarf, by rendering this image in smudged charcoal, Voss-Knude has blurred this distinction. If, as the original poster posits, the women around the protagonist have sold their personhood to a corrupt theocracy, this rendition retorts, how is Danes’ CIA agents’ allegiance to maintaining the American empire any different?

Around the corner from the listening space, in a darkened hallway on a black velvet pillow atop a pedestal, rests a crown of glass neon tubing – in a shape reminiscent of the Danish Emergency Management Agency (DEMA) logo – coursing with a blue electrical current that runs harmlessly toward the finger of those brave enough to cross the roped barrier to touch it. And in another room, a video plays of the journey taken by the boulder of rose quartz that rests on the street outside the museum; Voss-Knude’s answer to the terror blockades that adorn the town square “cunningly” disguised as flower boxes. You can see the spectacular stone from the exhibition space via a strategically placed telescope. Voss-Knude told me, after I spy him approaching the gallery via this surveillance apparatus, that on busy days it is remarkable to see how people interact with the stone. They touch it, stroke it and even kiss it. There is not really anyone around on the day I visited the gallery, but if it is true perhaps he has cracked the problem of having anti-terror defences that don’t fill the public with terror themselves in the way those produced by the commercial security industry do. However, as Voss-Knude points out, the unique properties of quartz have previously been utilized by the military to make battery-free radios as they convert radio waves into electricity. I can’t help but wonder if we have managed to step outside of the military-entertainment-complex at all?

However, any slight concerns one may have about the provenance of the quartz stone are dwarfed by the problematics of the prize piece of ancillary material Voss-Knude has scattered around the exhibition space. It is a document called “Krisøv 2017” (Crisis Exercise 2017), which was commissioned by DEMA to train through reenactment those who would respond to a terrorist attack in Denmark, and which Voss-Knude has gained access to, translated and made available to exhibition-goers. It is a piece of pulp fiction posing as a reasonable well-researched resource for security services. What is remarkable, however, is that this prose was ever convincing to anyone at all. This is especially true given that, when Voss-Knude interviewed the author of the document – the identity of whom he is reluctant to proffer lest the systemic critique of this project be turned into a witch-hunt – the author said he based most of the story on the show “Homeland”, which as previously mentioned has a controversial, jingoistic and racist way of depicting “the war on terror”. For Voss-Knude, this was something of a “Freudian slip” revealing the symbiotic relationship between depictions of Muslims-as-terrorists in the media and the limits of the military/intelligence imagination. While this connection is perhaps unfortunately predictable, what makes it all the more bizarre in a Scandinavian context is that the only example of a terrorist attack of the scale depicted in Krisøv 2017 was the massacre on Utøya in 2011, which was conducted by a Norwegian white supremacist. So one is left to wonder are the authorities preparing for actual threats or what they have seen on TV?

More unsetting still is the role that some kind of apparent sexual jealousy seemed to play in the production of this document, which one could argue has echos of an anxiety characteristic of white supremacist ideology itself (e.g the trop of “they are stealing our women”). In amongst all the tortured imagery of black/dark equals bad in the novella, we also find this description of an undercover would-be Islamic terrorist:

“He was small, but he was muscular, and his brown eyes and long curls had given him many benefits with the ladies over time. A lot of girls prefered a little, cheeky arb to the Danes with their inward bending knees, pale tattoos and transparent eyebrows.”

When quizzed as to why the author had chosen to include this, he told Voss-Knude that “he had been getting over a stormy relationship at the time” and the writing this had been “therapeutic”. Aside from the horrorshow of allowing the security services to develop anti-terrorism practices using a document so saturated with personal emotional pain – practices which will disproportionately affect the lives of thousands of people in Denmark with merely a tangential relationship to one particular religious tradition or who happen to have an ethnic background associated correctly or not with that tradition –, Voss-Knude points to another deeper problem. The fact that it resonated with its intended audience to the extent that the document was actually used for its purpose rather than scrapped as the piece of racist psycho-sexual melodrama it is, points to the wide appeal of the distorted world view it reveals. As Voss-Knude astutely points out in the foreword to the translation of “Krisøv 2017”:

“The deep personal insecurities adequately expressed in this text are the commonly perceived and propagated threats of multi-culturalism, immigration, a mainstream cultural incompatibility with the non-majority population, the erosion of male purpose and function, an erosion of white privilege, the emotional and organizational power of women and the corruptibility of all politicians.”

Voss-Knude argues that these postulates constitute a wider cultural atmosphere that renders the incoherence of a project like “Krisøv 2017” largely invisible to those who commissioned it. And it is with this wider and more complex view that Voss-Knude began to ask, who was actually responsible for the terror he was feeling?

The Anti-Terror Album is not Voss-Knude’s first engagement with the conditions of contemporary conflict trauma. Since the mid-2010’s, he has been working in cooperation with the Danish Defence Force on auto-ethnographic musical projects intended to break down the communicative gap between the traumatic and intimate experiences of combat veterans and the civilian world. This project titled both whimsically and multivalently, “Peter and the Danish Defence”, has resulted in numerous albums and performances with songs exploring the complex intersection of emotions that military service produces for those who go through it. The music itself on these records is diverse but with a kind of live orientation, suggesting it is meant to be experienced as moments of profound human connection. But where much of Vol. 1, particularly tracks like “March”, “You Trained me” and “I Don’t Read”, wouldn’t sound out of place on a Xiu Xiu record, Vol. 2 seems like an attempt to utilize the possibilities of pop, with disco ballads like “Let’s Talk about the Moon”, smooth jazz numbers like “Oh, The Fight” and indie jams like “Community of Risk”. But what stops these records feeling like a melange of influences is Voss-Knude’s masterly vocal performance, which provides a certain consistent, if multifarious, point of human contact. Secondly, there is also the way lyrical ideas weave their way through the record mutating as they go. For example, the notion of camaraderie between soldiers as love between men is articulated with a certain triumphalism on “Oh, The Fight” but on the later track, titled “The Love Between Men”, the idea now comes across with much more pain.

This technique has followed him on to “The Anti-Terror Album”, a record of unapologetic pop, drawing at times from R&B, electro pop, ballads, stadium anthems with some experimental sound collages to give the piece a conceptual through-line. All of these genre expressions have been given form by the deft production skills of Mads Brinch Nielsen, who somehow manages to give a certain consistency to the record while carving out a distinct identity for each track. It would seem part of this has to do with his control of the interplay of the bass element which strikes a perfect balance between intoxicating force and polished pop clarity. Part of what motivated this engagement with the genre was a desire to show that “pop songs don’t have to just be about heterosexual love”. Instead, Voss-Knude told me, he wanted to engage with pop’s capacity as a folk music to address the folk devil the political class have worked to transform Islamic terrorism into over the last two decades.

Nowhere is this motivation more evident than on the tracks “The Wound of Cinema”, which features vocals from the co-writer of many of the album’s songs, Angel Wei Bernild, and “The More”. The former, through its lyrical directness, static melodic lines juxtaposed with intense screaming, is reminiscent of the early work of Owen Pallett or the The Postal Service, whereas the latter is like a repurposed version of William Orbit era Madonna, for the purposes of a structural critique of media representation. These songs directly take on the feedback mechanisms between racist media representations and racist public attitudes that lead to the atrocious artefact that is “Krisøv 2017”. But the mood is then switched up again on the following track, “I’m begging you” which starts with a recording of a conversation about the media coverage of terror attacks before breaking into something carnivalesque, a la The Flaming Lips, with Voss-Knude singing, “I’m begging you, rewrite this shitty story”.

While the politics of this record are clearly critical of the state apparatus of anti-terrorism, Voss-Knude’s understanding of the problem is far from simplistic. He told me that actually more than anything he wants to communicate the feelings of doubt that surround these issues, and that it is largely the absence of doubt that makes anti-terrorism discourse so problematic. This is definitely reflected on the complex emotional journey of the record. He told me of the first time he played the finished record for his best friend and his sister and how the reactions of these listeners would change completely from one moment to the next. Listening to one song they would be dancing, laughing and shrieking for joy, but with the next track, they would be on the floor in tears or some confounding combination of the two. This is exactly what Voss-Knude is after; as he terms it “the crydance”. He sees the crydance as an opportunity for a release from the terrifying discourse and atmosphere of anti-terrorism. More than anything, he thinks this paradoxical response provides an opportunity for one to also get a sense of the absurdity and terror experienced by the muslims who suffer the direct consequences of misrepresentation. On top of this, in the throws of the crydance one can at once recognize the multiply entangled tragedies of terrorism and the wars nominally in response to it but that such mourning is insufficient if we are to overcome the impasse. Indeed, as important as it is to recognize the pain of this situation, to only focus on the catharsis offered by tears could easily lead back into the logic of violent reprisal with the purgation of emotional anguish providing merely the space to plan the for the next strike. This is why the tears must be met with dancing because dancing can complicate the simplistic narratives of the politics that surround terrorism. Through bodily intoxication with rhythm and bass, and the recognition of others around you undergoing a similar experience, the demarcations of political narratives can be confounded. The fragility of this fleshy existence is set against the potential ecstasy of communal corporeality. It’s an experience that no campaign promise can ever hope to capture. Kudos again here must be extended to Brinch Nielsen, who’s careful bass production has helped to make an album ostensibly about the problematics anti-terrorism discourse into something sexy. Or put more precisely, the record is able to utilize and expand the erotic capacities of pop music to libidinize (or make the listener feel deeply invested in and connected to) the project of dismantling the racist politics of anti-terrorism.

“Let’s talk about schizophrenia”, Voss-Knude said to me in the depths of our conversation. For him, this condition seems to perfectly encapsulate the entire issue of anti-terrorism. What got him thinking on these lines were conversations with soldiers during the Danish Defence project and the revelation of the Spotify playlists that they would use to pump themselves up while on patrol. While we find the usual genre suspects like aggressive metal (though I’m sure Rage Against the Machine would be less than thrilled about their inclusion), what strikes me as odd is the inclusion of the likes of dance-pop artists like Lady Gaga and Katy Perry. But then from the perspective of something like Steve Goodman’s Sonic Warfare, this makes perfect sense. The structured focus on bass and volume in these tracks can allow the listener to escape the sense of self that may otherwise cause one to hesitate in the infliction of violence or to become anxious with nothing but the sound of a desert breeze to listen to. Here we have the counter illustration of the insufficiency of crying alone. If tears without dancing can only serve to reinforce the existing narrative, then dancing (or dance music) without tears can, in these circumstances, only serve to help those doing the dirty work of nation states to disassociate from their actions. Playlists like this capture the schizophrenia of the war on terror as young soldiers are at once expected to be Western brand ambassadors and efficient killers; the music just helps to provide a more fluid transition between these modes of being.

“Safety is the Child of Terror”, is arguably the coup de grâce of the album. The title is taken from an appalling quote of Winston Churchill’s and serves as a perfect encapsulation of the infantile colonial mindset that permeates anti-terror discourse and leads to the production and acceptance as reasonable of materials like “Kriseøv 2017” and TV shows like “Homeland”. The track starts with a funeral dirge before the introduction of a disco beat puts the philosophy of this “great man” of history in his place as being incapable of understanding the wealth of human experience beyond narrow political self interest. Again, however, Voss-Knude is unwilling to let condemnation be the limit and wants to respond to the schizophrenic demands made of us (fear the terrorist just enough to feel safe to consume on the market) in kind. While performing the song at the release party, Voss Knude recounted to me how he broke into the song to say “Winston Churchill is Dead, but do you know what he said? He said safety is the child of terror. Now, I don’t know what that means but it’s really, fucked up!” But to avoid this momentary rant morphing into the two minutes of hate, he interrupted it with profound joyful silliness: “Let’s dance the pain away, shake your belly, shake your belly.” This again was the logic of the crydance at work. It is not enough to replace the folk devils put before us by the political system with more critically defined folk devils. We need a sense of joy to strive for together beyond this terror.

It is a striking and unusual thing to have a pop album be the centerpiece of an art exhibition but it speaks to the nature of the problematic Voss-Knude sees as central to our time. He told me that he doesn’t feel he and his work fits well into the art world or the pop music world. However, for him, and I am inclined to agree, neither of these fields seems up to the task of navigating the issue of terrorism on their own. On the one hand, as already mentioned there is a pervasive idea that pop music is only good for hetrosexual love songs. On the other, the art world may be producing incisive critiques of problematic discourse for the cultural elite but very few people actually get to incorporate them into their day to day lives. Meanwhile popular TV shows like “Homeland” are filling the heads of future centrist politicians and their voters with a racist understanding of terrorism. So I admire how Voss-Knude has worked to game the system, by using the autonomy afforded to him by the art gallery to make and promote a record anyone can listen to on the streaming service of their choice. His work may even find its way onto algorithmically generated playlists and for a moment he will be able to whisper in the unsuspecting listeners ear: “I re-focus on what threats to keep. Wealthy castles are floating by and immigrants are blamed for this injustice. It’s a decoy”.

When Voss-Knude tells me he is thinking about moving into reality TV, I’m not surprised. As an artist his work has been characterized by putting himself forward to meet people where they are while not compromising what he believes and knows to be true. As we parted, my mind was awash with the possibilities of this one man insurgency coming to disrupt the comfortable black and white narratives upon which so much of this nation’s politics is based. But even with this disruption he would be coming to them with the kind of openness that is actually required to win “hearts and minds”. I look forward to catching a preview for his appearance on a mainstream TV show as he introduces the audience to the crydance.

Info: The exhibition “The Anti-Terror Album” is open until May 6 at Museet for Samtidskunst (Museum of Contemporary Art) in Roskilde.“The Anti-Terror Album” was released January 20 by the museum.