Struer Tracks – Environmental crises and spiritual experiences through the perspective of sound art

By Mikkel Schou, photos by Mateusz Szot

On paper, Struer Tracks is a bit of a radical experiment. A sound art biennale with a host of experimental and international artists in a small and remote port town in West Jutland seems unlikely to be a smash hit. Traveling to Struer, I wondered how big of a crowd previous iterations of Struer Tracks drew and what would happen this year. And for a skeptical city-person like myself, it’s almost too easy to imagine Struer Tracks as something between a local curiosity and a niche attraction for hardcore sound art enthusiasts. Oh boy, was I wrong.

In the past, the biennale lasted for a few weeks and focused almost exclusively on presenting installation works. However, under new leadership, Struer Tracks has transformed into a compact five-day festival dedicated to sound and listening. This year it consisted of two supplementary parts: a thoughtfully curated sound art exhibition and a dynamic performance program featuring artists seemingly indifferent to the divide between sound art and music. And what a festival atmosphere! What’s up with Struer? In fact, it’s probably a better city for this kind of festival than Copenhagen, where it’s so difficult to present art situated in formats way off the beaten track. In Struer everything seemed possible, even getting the locals engaged. At least every performance was packed. And they seemed to like it – at least one elderly lady remarked to me, after experiencing Dalin Waldo’s deeply original and highly intense lecture/performance on eloptic energy and emotional machine activation, “You know, it’s pretty good to get your mind blown once in a while when you’re retired”.

Resonating bones in The Cube

Let’s rewind to the night before. I found myself seated inside “The Cube,” a unique space known as a ‘near’ anechoic chamber, where technicians from Sound Hub assessed the frequency response of new speakers. At its center, a small performance set up: a mixer, laptop and a modular system, around me a quadraphonic PA system featuring world-class d&b speakers. And oh my God, this room just sounded.. ridiculously good. What a find. And to think no concerts have been held here since 1982!

The program note told me that it’s a new piece using a sound synthesis method developed by the artists that is able to abstractly describe geometrical ellipses. So it basically told me nothing, as it read like something straight out of a convoluted artistic research paper.

First up was Max Eilbacher presenting PLUS (Axis of Distance). The program note told me that it’s a new piece using a sound synthesis method developed by the artists that is able to abstractly describe geometrical ellipses. So it basically told me nothing, as it reads like something straight out of a convoluted artistic research paper. To be fair, it kinda sounded like that too – nice but all over the place.

The next performance by Eau Pernice was much clearer conceptually. Three singers were recorded singing for 25 minutes of what sounded like a mixture of vocal sounds and backwards words, the recording was then reversed and played back. The crowd laughed heartily when they recognised famous lyrics, but in fact the works’ conceptual worth became most apparent when it highlighted how the reverse transcription and playback has reshaped everything and rendered the language (now double reversed, so a sort of false positive) unintelligible, and centered on just how important pronunciation, accentuation, and melodic contours are for our understanding of language.

Perhaps it was because my bones were resonating, but I felt a physical and emotional connection to the material and to the performance.

For the final show in The Cube, Serge-wizard Thomas Ankersmith took the stage. Using a very limited selection of material, almost all of which were performed live, his performance felt simultaneously chaotic and focused. It channeled an improvisatory, erratic and unpredictable energy, yet it also adhered to a clear structure and development. Especially mesmerizing was a whole section of phantom sounds making an evocative melodic layer directly inside my head, while the rest of the room was pulsating with noise and sub. Perhaps it was because my bones were resonating, but I felt a physical and emotional connection to the material and to the performance. It was an interesting contrast, undoubtedly staged by the curators on purpose. As the possibilities of computers continue to expand and border on the seemingly infinite when it comes to audio manipulation, it seems ever so meaningful to consider how this affects the artists interacting with them, what they value in their art, and how it’s experienced by the listeners. Here was a master instrumentalist, employing a conceptually traditional approach in which skill and dedication were the guiding principles, and absolutely killing it on his 50 year old modular synthesizer, while the evenings earlier synthesis innovation had felt convoluted and trite.

Musings on ecological crises and technological annihilation

The next day, I checked out the installations. Walking into Struer’s Lystanlæg (a recreational park), my friend enthusiastically spots a strange mushroom. Upon closer inspection, we discover that it’s actually a small robot – just slightly resembling a mushroom with its conical shape. The robot is known as a Komorebi and it’s built by artist duo Matteo Marangoni & Dieter Vandoren. And the park is absolutely full of them. Depending on sunlight, cloud cover, and shadows from the trees, these little robots generate sounds. Together they feel like an omnipresent swarm of peculiar creatures communicating through long, ethereal tones and clicks. The pervasive soundscape made me wonder how noisy the park would be without them—had the Komorebi temporarily taken over, excommunicating all the insects and animals? Or is the general loss of biodiversity so severe that Danish parks have just fallen silent?

A small wooden house on the harbor pier, with beautiful views of Limfjorden, was the setting for Crenulations – Pacific Drift. This work, based on field recordings from the Pacific Islands and interviews with indigenous elders, focused on listening to ecosystem changes during our current ecological crisis. It was exemplary in its respectful artistic approach, yet it was perhaps so subtle that the central theme – climate change in the Pacific and its impact on local communities – seemed almost extraneous and anonymous. And occasionally, the custom-built B&O subwoofer bench (despite being very cool) muddled the mid-range frequencies to the point where it was nearly impossible to comprehend the content of the interviews.

It was an unexpected delight and a refreshing approach to community outreach and audience engagement.

Heading to the slaughterhouse, Dansk And (Danish Duck) where the rest of the installations were, I took refuge from the rain at the Living Radio Lab. Coming right at the time when the Shortwave Radio Collective conducted their daily DIY workshops, they kindly helped me in constructing a DIY radio receiver using a discarded toilet roll, a small iron bar functioning as a diode, and basic electronic components. It was an unexpected delight and a refreshing approach to community outreach and audience engagement. At the slaughterhouse, Sól Ey equipped visitors with The Electromagnetic Sense, a device comprising a chest-mounted transducer and a handheld electromagnetic microphone designed to make users physically and audibly aware of the ever-present electricity. The sound of rechargeable battery packs, in particular, felt almost too much like techno music to be true.

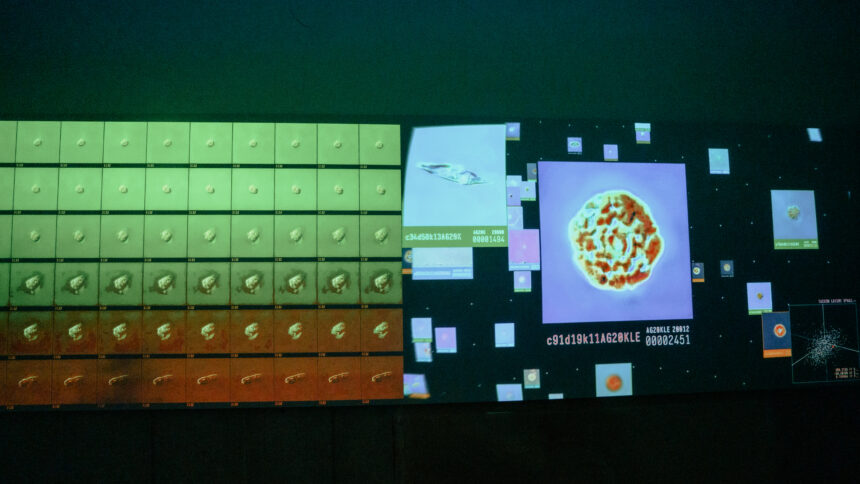

Installed in the slaughterhouse was Færgetid by William Kudahl, a heartfelt audiovisual work and a short slice of slow cinema about two local ferrymen, their lifelong friendship and musings on life in rural Jutland. Codex Virtualis_Genesis by Interspecifics set out to create a real time algorithmically determined digital ecosystem with bacterial-AI-organisms appearing endlessly in a visually impressive audio-visual staging that felt conceptually strong, but perceptually superficial. And a few of the Komorebi made a return in a completely controlled environment, where timed lights and long leafed plants activated by electrical fans framed their sonic behavior in a way that could easily be perceived and which satisfied my intellectual desire to understand their programming.

It points to our present and to our society where everything is becoming oppressively digitized, and asks the question; how does that change our identity, values and relationships to others and the natural world around us?

Like the other works, these too thematically engaged with the world around us, exposing either the world’s incredible complexity hidden in plain sight, such as electromagnetic waves, or situating our lives in historically cultural/digital context through presenting personal stories of a lived life, in which the idea of values seem so old fashioned that they’re on the brink of extinction, and science fictional musings on the future of bacterial organisms in a world entirely transitioning to the digital. It points to our present and to our society where everything is becoming oppressively digitized, and asks the question; how does that change our identity, values and relationships to others and the natural world around us? And how do we navigate our intense codependency on ubiquitous technologies that simultaneously provides us with quality of life, access to information, entertainment, media and art, but also surveil, monetize and selectively curates our media consumption through systems designed to make us totally addicted?

Explorations of the non-human and a myriad of organs

These themes were also present in the performance program, especially in Mélia Roger’s A Celebration of Missing Sounds. As I was sitting outside in a very slight rain and listening, I had a moment of weird cognitive dissonance as it dawned on me that the persistent wasp which has constantly been buzzing around my head for the last few minutes, was of course only present in the field recordings. Citing both Donna Haraway and Karen Barad in her research, Mélia Roger created pieces that deeply engaged with the sound of the surrounding ecology – a kind of ecological sound therapy – and she had a spectacular ability to bring her audience to the heart of it and make them stay with the trouble. Both in this and in another performance work at Struer Tracks, Intimacy of Lichens, in which she explored the sounds of the non-human through microphones worn on her hands – live-performed for an audience wearing silent disco headphones.

It was as close to a spiritual experience as any I’ve had with sound for a long time.

My report from Struer Tracks concludes with the only performance of the entire festival situated in a traditional concert venue. Robert Curgenven is, amongst other things, an organist and so he needed an organ to perform. But not just one, as he humorously and unceremoniously explained before the event, several organs – or recordings of them at least. I was a little skeptical as organ music, even multiple organs played simultaneously and tuned microtonically apart, makes me think way too much of classical music. But the next hour was a marvel. Massive sonic textures, tectonic plates of intricate beating, and a stringent, minimal and conceptually honest approach to material. It was as close to a spiritual experience as any I’ve had with sound for a long time. And when I heard SUNN O))) play a few weeks later in Copenhagen, I couldn’t help but think that drone metal can be done even better with a church organ and four speakers in Struer.

Info: Struer Tracks took place on the 23th-27th of August. Mikkel Schou is a Copenhagen-based artist and co-director of the yearly festival MINU.