Kirstine Lindemann – Movement that carries an inner state

Performance recommendation by Macon Holt

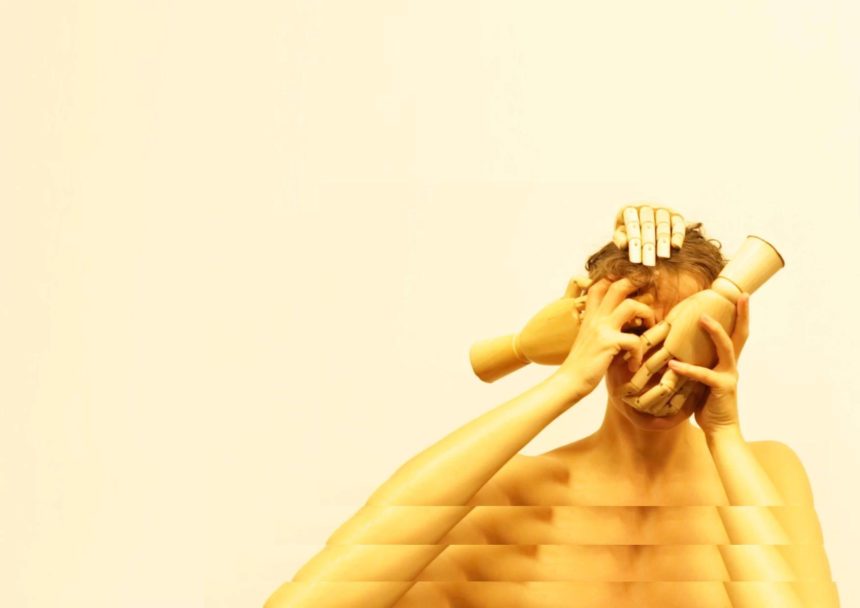

Later this month, Danish composer, performer and recorder player, Kirstine Lindemann, will start a tour of Denmark to showcase a collection of both earlier and new compositions with collaborators Yiran Zhao and Irene Bianco amongst others. Known for previous work such as the piece Breath (2018) and her ongoing project with Zhao, OTHER EYE, Lindemann is an artist who’s central concern is the limitations and the possibilities of connection posed by the body when it is understood as a musical instrument.

Breath, when performed two years ago at Bådteatret in Copenhagen, saw this methodology taken to some intriguing if uncomfortable places. By utilizing her woodwind training she made the rhythms, responses and affects of respiration – run through the disorienting processes of digital manipulation – into her musical material. After performing a series of what looked like exhausting aerobic jumps, the panting of catching her breath set the tempo for an embodied exploration of sonic expression and human connection. As her breathing became more laboured while maintaining a regular meter, the performance morphed from an exploration of exhaustion into something similar to a panic attack. Further still down this path, the subtle communicative possibilities of breath became all the more complex as it seemed to oscillate between agony and ecstasy. In the final section of the piece, Lindeman took it into more troubling territory by restricting her breath with cellophane. But even in this frightening scenario and the dangers inherent in playing with one’s breath, Lindemann always somehow managed to maintain an atmosphere of artistic exploration. It was a testament to Lindemann’s discipline and abilities as a performer when the stakes were so high that she was at once able to gesture towards what it would be to lose control but at the same time imbue the audience with the confidence that she was entirely in control.

Indeed the complex emotions and responses stirred up by the corporeality of a piece like Breath are somewhat secondary for her. Her main interest in this bodily form of music-making is the field of connection it seems to open up between the body of the performer and those of the audience members. When so much of our world seems to operate by denying the bodily nature of personhood, Lindemann’s work is an attempt to short circuit this ideological separation and allow for a kind of shared communicative experience. As Lindemann explains it:

“Many times when performing the piece I noticed that the audience would copy the movement of my breath – they would hold their breaths with me or even copy strong and big body movements without being aware. This fascinated me big time. I started to read about mirroring neurons and started wondering how this applies to a performance situation: How do I as a composer and performer relate to my audience? and which role does my physicality play in this? When we copy someone else’s body language or movement, I believe we don’t only copy the physical movement; I think the movement carries an inner state too—that when we mirror we allow the other to mould our state of mind through the physical impact. Maybe a bit like when we let ourselves be carried away by music.

For me, when performing music, it’s about sharing something and getting to some kind of state where we are beyond whichever barrier of culture, personality or background there might be between us. I don’t think it’s possible to map out exactly how this physical connection between the performer and the audience works – I think it is different in every piece and every setting, but I do feel that working physically in a music setting creates a very special channel to meet my audience and communicate with them. After all, we all have a body.”

Lindemann has further developed the possibilities of physicality as a means of musical connection in her work with the composer and performer, Yiran Zhao, through the project OTHER EYE. As a duo, the two them explore the possibilities and impossibilities of synchronicity: While following precise unison choreography, Lindemann and Zhao use contact microphones to amplify the differing textures and topographies of their bodies and clothing, and the (ir)regularity of their blinking as their lashes flutter. The complex interrelationship of these differences is given an exploded view in later sections which see them utilize video feedback to illustrate the disunity of a communicative gap and the anxiety this can produce. But what makes this an interesting take on the problem of communication is the way that the piece situates this gap as only one possible or partial experience of communication rather than its intrinsic nature. Indeed we are constantly presented with counter-arguments to that grey and conservative view of communication between beings as impossible through the use of humour and clear camaraderie that permeates each moment of the performance.

The performance series starting later this month is entitled Who is the third who walks always beside you? and takes its name from T. S. Eliot’s poem, The Waste Land. After reading the full stanza from which the line is taken on Lindemann’s website, I was struggling to draw a connection from the title to what I know of Lindemann’s work. Who is the third who walks always beside you? If I can be permitted a momentary theoretical indulgence, I would like to suggest that this third is that latent virtual potential inherent in the interaction between beings who mistake themselves for being separate individuals. The third is that place we can occupy and invent together once we drop the defences that are required to move through so much of the world. Lindemann’s work is a daring attempt to intensify and draw you into such a space. It’s an invitation and one that is well worth accepting.

Kirstine Lindermann and company will be on tour in Denmark on the following dates and location: 24.02.20 at Saftstationen i Damme on Møn, 27.02.20 at Kunstmuseum Brandts in Odense, and 01.03.20 in Koncertkirken in Copenhagen.