Festival of Endless Gratitude 2020 – Opening the windows of the mind (live report)

Festival of Endless Gratitude, Koncertkirken, Copenhagen, September 10-13 – live report by Wieland Rambke

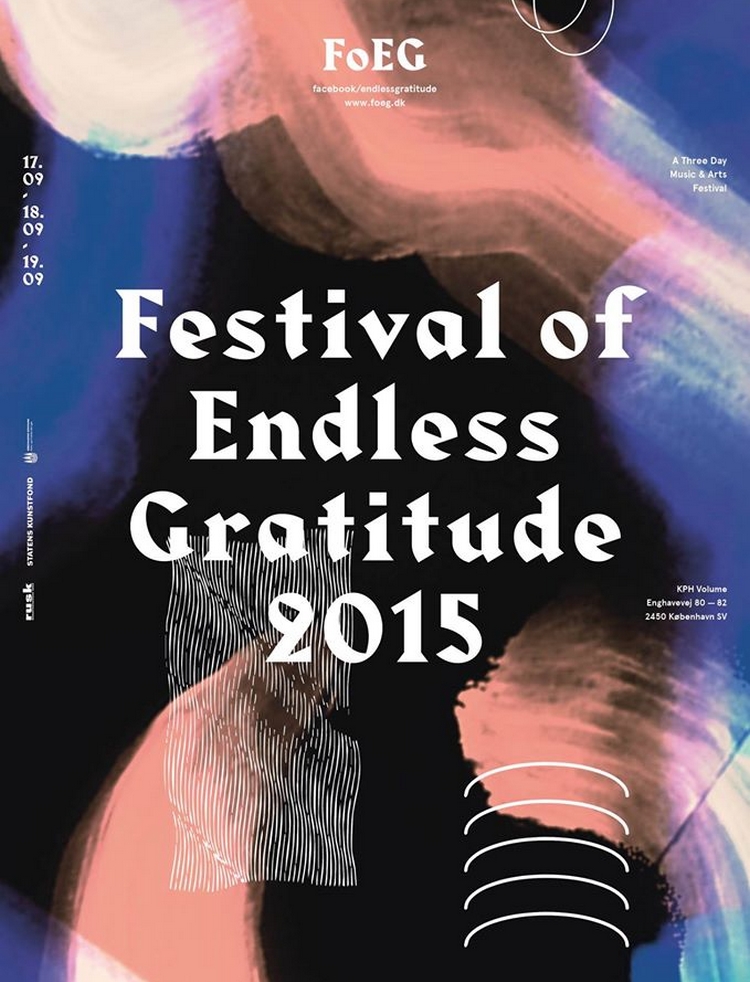

For the 13th year now, Festival Of Endless Gratitude opened its doors for an adventurous audience. What today is a festival celebrating experimental music from around the globe has gone through a long history of changes now: Originally a festival with a focus on New Weird America and outsider folk music, FOEG has gradually expanded into a true feast for those who enjoy sonic expeditions into wildly different directions.

For long, the organizers were uncertain whether or not the festival might at all be held under the current set of Covid-19 rules. But luckily, Festival Of Endless Gratitude finally came about. They were forced to scale down, though: Traditionally held at KPH Volume, this year’s edition of FOEG found itself at Koncertkirken in Nørrebro. And yes, it is weirdly funny when an event is held at a secularized church, only to be opened with a sort of quick sermon on the regulations regarding Corona: Thou shalt remain in your assigned seat. Thou shalt follow the arrows on the floor. Thou shalt not loiter at the bar. Well, what can you say, 2020 certainly is a special year. The smell of disinfectant has daily life for us all. Who would have thought?

As always, FOEG has chosen artists who for the most part are operating under the radar, artists dedicated to realizing their vision on their own terms, artists who have nothing to prove and all to give. The common aspect for the artists assembled is an unbridled love for the possibilities of music.

Blake Hargreaves opened the festival with a set of miniatures played on the churches’ own organ. He has been performing research into the properties of church organs across the world for a while now, bringing out their individual quirks, and combining his findings into semi-improvised performances. At times somber, at times humorous, these miniatures played out between deep, rumbling drones, and refreshing sprinkles of high-register notes. Trees swaying in the breeze were projected onto the walls, and sometimes I felt reminded of the old 90s role-playing games I used to play as a kid, what with the conjunction of mystical notes from the organ together with the projection of trees where you could see every pixel. Maybe I was just playing too much as a child. You can’t blame me though: „Secret of Mana“ was a really good game!

Later, guitarist Raphael Rogiński played healing music from the Jewish tradition of 18th Century Ukraine and Poland. The gentle instrumentals had the esoteric, yet very concrete purpose of rekindling the life energy of the ailing. Re-interpreting traditions means to keep traditions alive, and this project is not dedicated to mere preservation: Instead, it is giving new life to the rich musical tradition that he has chosen to work from. It made me dream.

By the time that Bankerot entered the stage to perform his solo work „Vampyr“, we were deep into the night: Elegic, romantic and melancholic, like vampires themselves are, these compositions work really well as a soundtrack to Carl Theodor Dreyer’s silent classic „Vampyr“ from 1932. I tried it out when I got back home, playing the album while watching the film, and I can only recommend you try it out yourself. The two work really well together.

Lamin Fofana began the second evening with a dense set of ominous and ghostly tones. Taking a DJ’s approach to his performance, he was mixing his own musical stems with heavily-processed samples of jazz music and other „secret records“ as he called them, choosing not to disclose them in a chat we had after the gig. Heavy on delays, the performance was contracting and expanding in time. A sequence of scattered drum hits coalesced into a rhythm section that seemed to stumble around itself, echoing the often loose, yet very tense feel of free-jazz drumming. He later complained about some screw-ups during the concert, saying that not having played live in 6 months had hampered his performance, but that wasn’t obvious to the listener: In fact, the voice sample he used that had accidentally turned out garbled and truncated during the concert was a perfect fit for a set of cryptic sequences that refused to stay in one place for too long.

With his interpretation of „Trio om tiden der gik“, originally a composition for recorder, cello and piano by Danish avantgarde composer Henning Christiansen, Anders Lauge Meldgaard has undertaken a meticulous process of transcribing the original piece into a composition for 12 instruments, entitled „12 instrumenter til Henning“. Meldgaard chose to let each instrument play at a different tempo, creating a flurry of notes brimming with energy, refracting the original composition into individual strands like light broken up by a prism. This was complemented nicely by a projection of the notation that had been processed through a kaleidoscopic algorithm. Performed by Adam Woer on the flute with Anders Bach and Anders Lauge Meldgaard helming the electronics, the result was a tight performance with a unique charm.

The night drew to an end with Minais B, who played a somber and dreamy set of drones and arpeggios on organ and synthesizers, drawing inspiration from traditional Danish hymns and church music.

As a whole, the festival had a tendency towards ghostly and meditative music, as exemplified by the feverish compositions of Saturday’s first artist, Marja Ahti: Warped tones featured extensively. I heard lots of modulated sine waves and complex noise spectra together with natural field recordings. Sonic texture is a focal point of her body of work. A diffuse and dread-filled atmosphere unfolded; Ahti’s music creates the paradox of claustrophobic landscapes.

Lieven Martens seems to apply similar methods, but to a wholly different end: Employing sampling and recording techniques like an instrument, his music is a wondrous and intimate excursion into the more blissful forms of ambient, and his performance here was no exception.

It was time for what undeniably was the biggest name on this years line-up: Manuel Göttsching, the famed composer who originally made a name for himself as the guitarist of seminal krautrock outfit Ash Ra Tempel. Together with the Danish guitar sextet Cirklen, he performed a reworked version of his legendary 1974 record, „Inventions for Electric Guitar“. The composition, released in 1975, was originally played and recorded by Göttsching alone. In the composition, tape delay features heavily not as an audio effect, but as a compositional tool: Individually played notes are layered with the echoes of the notes played before, gradually creating chords. „Inventions…“ is a game of adding and removing notes in an ever-going cycle. And by virtue of this inherently gamelike aspect, the piece lends itself naturally to be played in a group.

For the performance with Cirklen at FOEG, the original notation had been expanded and reworked for 7 guitars. Instead of the tape delay apparatus, it was the players themselves who picked up on each others parts, overlapping and replaying their notes, processing the original piece through a form of instantaneous, crossreferential network. This opened up the piece for a more free-form interpretation: Instead of notes merely being echoed, all players applied varying techniques to their playing, with bent notes and palm-muted strings creating ever-more complex layers, chords and variations, embellishing each others playing with ever merely falling into repetition.

„Inventions“ provides a basic structure to work from, where every performance becomes unique. Instead of a tight and rigid notation, „Inventions“ is a framework. And beyond the technical, it is open for intuition and spontaneity. It was obvious that Göttsching and Cirklen have performed this together before and, thus, have sharpened their understanding of each other. Every member in this performance enjoyed the full trust of their peers. This collective strength created a performance of pure magic.

Gate Hand, consisting of Claus Haxholm and Francesca Burattelli, was something I was looking forward to: Haxholm is a household name within the Danish music underground. For more than a decade now he has produced a steady flow of releases, from black metal and dungeon synth to poetry-infused sound art ventures all the way to his heavy-hitting electronic music work under the name Assembler. Gate Hand is a joint project with musician and performance artist Francesca Burattelli. The duo played a highly suggestive blend of drones and jagged beats. Vocals were plentiful, from humming to screaming. I felt reminded of Thought Gang, the musical child of David Lynch and Angelo Badalamenti: Not so much by superficial similarities, but rather since both formations are composed of two individuals from very different backgrounds who clearly know how to communicate with each other to create a third, shared space. Both acts excel at a form of intuitive story-telling, and they share a sensitivity for all things gothic and industrial; not as music genres, but in terms of imagery and emotions evoked.

The final day of FOEG was opened by composer Sandra Boss, who performed a live-rendition of her work „Luft“. Using a self-built organ apparatus driven by MIDI-controlled motors and airtubes, she played „Luft“ in a new form, different from the original release, but equally as captivating. When the motors rev up, they become part of the composition itself. „Luft“ („Air“) is clearly the topic of this piece, where short bursts of notes and long, drawn-out drones are charging the room with a mesmerizing atmosphere.

As Katrine Grarup Elbo closed the festival with „Slutsang“, we were presented with a circle of songs for 5 voices that Elbo accompanied on the violin. Later, a piano joined in. The lyrics were based on fragments by Danish poet Julie Mendel, while the vocal parts drew heavily on Nordic folklore. Lots of frozen reverberations and looped sequences adorned this performance of quietly longing songs, with Elbo’s violin playing sickly-sweet miniatures that at times would be dispelled by gut-wrenching screeches from her choice instrument. And thus, a festival of adventurous exploration came to an end.

When I talked to Manuel Göttsching about his concert, he related what it was like growing up in post-war West Germany where the 50s were a time of denial and silence. Culturally, this was the high-period of Schlager and Heimatfilm, sentimental productions that channelled and communicated absolutely nothing, and whose sole purpose was to entertain in the most harmless way possible. Platitudes became the standard, and there was no place for confrontation or exploration. Films and music of that time evoked a drowsy world of safety and security, with a particular fondness for alpine backdrops. Kitsch ruled everything, and rock and roll in West Germany had no identity of its own, instead only trying to emulate the American idols: Tame and pale copies of the originals of the U.S. And the U.K. delivered the illusion of originality, yet it was never more than a bloodless simulation. This atmosphere denied reality and the world itself – it was administered escapism. It was this suffocating atmosphere that Manuel Göttsching grew up in, and it was from this context that a new generation of young Germans would go all-in for experimentation, opening up the windows of their minds to let in the fresh air of a new day. This generation found new and unknown paths for itself, creating their own work based on what was uniquely their own vision, instead of merely chasing the next prescribed fad. And still in the 70s, West Germany lacked any fundamental business structure for rock music, and it was precisely this lack which had made the free explorations of the so-called Krautrock acts possible.

Funnily enough, Manuel Göttsching re-interpreted this very term in the interview: „Kraut“ as a German word means weed, or plant life that grows uncontrolled, and that is how he defined the era of 1970s rock music in Germany: As a wild forest where things came about organically, without any need for justification, free from mercantile motivations. From the beginning of rock and roll with Elvis Presley, American and British acts had been under the tight control of their managers. It wasn’t until Jimi Hendrix had started his own independent studio in New York that he would finally gain the freedom he had sought for many years, yet the interests of his shrewd management still pushed him from concert to concert. Likewise, by their third album, the Doors found themselves locked into a grinding process of manufacturing songs in the studio to keep up with their contractual obligations. Groups from America and Great Britain had to produce for a defined market, and for the commercial interests of record executives.

There was no such market or business network in Germany at the time, and Manuel Göttsching remembers this as an egalitarian period of freely flowing creativity and exploration. Roadies would be managers would be agents, and I couldn’t help but see a similar spirit in Festival Of Endless Gratitude: A festival driven by nothing else but a great love for great music.